Divine Mercy and the Monastic Vocation

Disclaimer: The series of letters entitled “Correspondence on the Monastic Vocation”, while based on the real questions of a number of men in various places and states of life, is entirely fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons, institutions, or places is purely coincidental.

Disclaimer: The series of letters entitled “Correspondence on the Monastic Vocation”, while based on the real questions of a number of men in various places and states of life, is entirely fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons, institutions, or places is purely coincidental.

Letter XXI: Wilburt

Dear Father,

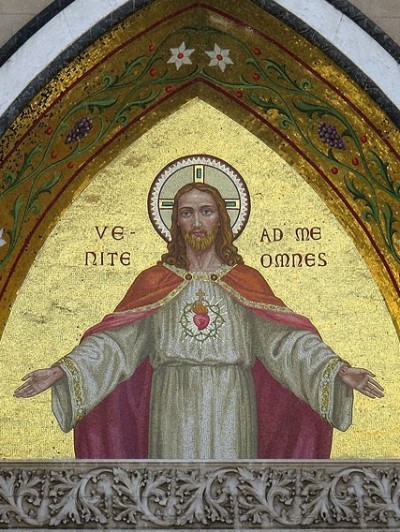

The more I think about my own life and the life that, I think, lies ahead of me in the monastery, the more do I come to see that it is all about mercy. I have been hearing a lot of talk about mercy lately. There are posters on every door of my parish church showing an image of Christ, arms open wide, with the text: “Mercy is waiting for you inside. Come in”. I suppose that the same poster could be put on the door of the monastery.

I remember hearing you explain on one of my visits to Silverstream (I think it was in the Chapter that you allowed me to attend) that mercy is what happens when God takes a man’s misery to His Heart. Your explanation stayed with me. God knows that there is a load of misery in my life. Sometimes I feel that I will never get out from under it. The same old temptations come at me, and I fall into the same old sins. My biggest temptation is to say to myself, “Give up. You’re not fit to call yourself a Catholic, let alone a monk”. Sometimes I feel steeped in sin.

Anyway, I have been praying about the mercy of God and offering him my misery. My question is this: When is a chap’s misery so irredeemably miserable, that even God says to him, “Move along. You’ve exhausted your quota of my mercy. I have better people on whom to lavish my grace”.

Sometimes I see myself as a Benedictine, looking very smart in a black habit and happily following the monkish routine. At other times I see myself as a dreamer who has deluded himself into thinking that a monastic vocation is within reach. When you have a moment, Father, would you write me something about this whole mercy question? How do Benedictines understand it? Should I take the plunge or not? Into mercy? Into the monastery?

Wilburt

Dear Wilburt,

You are too young to remember Saint John Paul II’s encyclical on Divine Mercy. You were not even born when the encyclical was published thirty–eight years ago on 30 November 1980. It was entitled Dives in misericordia, “God, rich in mercy”. At the time, the encyclical resonated in the hearts of many as an invitation to return to the Father and to believe boldly in His tenderness for the most fragile and wounded among us. Saint John Paul II was touched to the quick by the message of his humble compatriot, Saint Faustina. The Pope from Poland was compelled to share her message with the whole Church and, indeed, with the world. This he did, not only by his teaching, but also by integrating Saint Faustina’s message into the liturgy itself by instituting the Feast of Divine Mercy on the Sunday after Easter.

For us Benedictines, the mercy of God is something that surrounds us on all sides. It is above us and below us; it precedes us and follows us; it lifts us when we fall and sustains us in the midst of life’s uncertainties. Saint Benedict uses the word misericordia seven times in the Holy Rule. Misericordia is, as you rightly remember, that quality of love by which one takes to heart the misery of another. Seven is the mystic number that signifies fullness, superabundance, and completion. Benedictine life is a school of Divine Mercy.

The origin of every Benedictine vocation lies in the mystery of the mercy of God. When a man seeks admission to the monastery, it is because the mercy of God has broken through the crusty outer shell surrounding his heart, and penetrated into the secret places of his inmost being. A man knocks at the door of the monastery because he has recognised that God, in His mercy, has, as the psalmist says, “prepared a home for the poor” (Psalm 67:

He is a father to the orphan, and gives the widow redress, this God who dwells apart in holiness. This is the God who makes a home for the outcast, restores the captives to a land of plenty, leaves none but the rebels to find their abode in the wilderness.(Psalm 67:6–7)

If a man finds himself, willy–nilly, before the cloister door waiting to be admitted, it is because God has shown him mercy. If a man discovers the wisdom and sweetness of the Rule of Saint Benedict, it is because God has shown him mercy. If a monk perseveres in his vows, it is because God has shown him mercy. With Our Blessed Lady, every monk can say, “He hath received His child Israel, being mindful of His mercy” (Luke 1:54). You must discover, Wilburt, that you are that child Israel, dear to God, and lifted up to be pressed against His Heart.

Wilburt, if you do, one day, enter the monastery, and receive the habit, and make vows as a monk, your profession will be, not a display of your shining virtues but, rather, a public act of abandonment to the Mercy of God: “Receive me, O Lord, according to Thy Word, and I shall live; let me not be disappointed in my hope” (Psalm 118:116). You will throw yourself, boldly and blindly, into the arms of Divine Mercy, imitating the Oblation of Jesus from the altar of the Cross: “Father, into Thy hands I commend my spirit” (Luke 23:46).

Speaking for myself, Wilburt, I can say that my life as a monk is nought but a glorification of the Mercy of God; it is an act of praise. By my life at Silverstream, hidden though it be, I am saying to the whole world: Misericordias Domini in aeternum cantabo, “The mercies of the Lord, I will sing forever” (Psalm 88:2). And with Jesus, the New David, I am intoning a new hymn of praise: “I confess to Thee, O Father, Lord of heaven and earth, because Thou hast hidden these things from the wise and prudent, and hast revealed them to little ones. Yea, Father, for so it hath seemed good in Thy sight” (Luke 10:21).

What do we find in the seven references to Divine Mercy in the Rule of Saint Benedict? I propose that you follow me in tracing the references to mercy, by going through the Holy Rule from back to front. Each reference to Divine Mercy is a kind of step towards the altar where, on the day of his profession, the Benedictine monk throws himself into the embrace of God and, by the grace of the Holy Ghost, unites himself to Christ, Victim and Priest.

Let him that hath been appointed Abbot always bear in mind what a burden he hath received, and to Whom he will have to give an account of his stewardship; and let him know that it beseemeth him more to profit his brethren than to preside over them. He must, therefore, be learned in the Law of God, that he may know whence to bring forth new things and old: he must be chaste, sober, merciful, ever preferring mercy to justice, that he himself may obtain mercy. Let him hate sin, and love the brethren. And even in his corrections, let him act with prudence, and not go too far, lest while he seeketh too eagerly to scrape off the rust, the vessel be broken. Let him keep his own frailty ever before his eyes, and remember that the bruised reed must not be broken. (RSB, Chapter 64)

Saint Benedict says that the abbot must be merciful, ever preferring mercy to justice, that he himself may obtain mercy. Look to your own life, Wilburt. You will discover innumerable occasions on which to prefer mercy to justice. Only in this way will you have a claim to mercy for yourself. Learn to be excessively merciful, for to those who are excessively merciful, God will show an excessive mercy.

Let the Abbot pour water on the hands of the guests; and himself, as well as the whole community, wash their feet after which let them say this verse: “We have received Thy mercy, O God, in the midst of Thy Temple.” Let special care be taken in the reception of the poor and of strangers, because in them Christ is more truly welcomed. For the very fear men have of the rich procures them honour. (RSB, Chapter 53)

Here Saint Benedict describes the rituals of monastic hospitality. In doing this, he quotes the psalmist: ““We have received Thy mercy, O God, in the midst of Thy Temple” (Psalm 47:10). Silverstream Priory is one place wherein the mercy of God is poured out upon all who come to receive it, but there is no need to travel to the east or to the west, to the north or to the south, in search of a place where Divine Mercy is poured out. In every place where there are hearts in need of the mercy of God and open to receive it, mercy will be given, rising all radiant against the darkness “like the Dayspring from on high” (Luke 1:78).

Although human nature is of itself drawn to feel pity for these two times of life, namely, old age and infancy, yet the authority of the Rule should also provide for them. Let their weakness be always taken into account, and the strictness of the Rule respecting food be by no means kept in their regard; but let a kind consideration be shewn for them, and let them eat before the regular hours. (RSB, Chapter 37)

Saint Benedict speaks here of the mercy that human nature readily shows towards the very old and the very young. For Saint Benedict, Wilburt, every weakness constitutes an irrefutable claim on Divine Mercy. Remember that. At certain seasons and hours in life, we ourselves are the weak ones in need of mercy, and at other seasons and hours, we are the instruments of Divine Mercy, the finite channels through which the pity of the Heart of Jesus reaches others to soothe, to comfort, and to heal them.

As it is written: “Distribution was made to every man, according as he had need.” Herein we do not say that there should be respecting of persons – God forbid – but consideration for infirmities. Let him, therefore, that hath need of less give thanks to God, and not be grieved; and let him who requireth more be humbled for his infirmity, and not made proud by the kindness shewn to him: and so all the members of the family shall be at peace. Above all, let not the evil of murmuring shew itself by the slightest word or sign on any account whatsoever. If anyone be found guilty herein, let him be subjected to severe punishment. (RSB, Chapter 34)

Here Saint Benedict tells us how we are to act when mercy is shown us. We are to receive it humbly, gratefully, and simply, not as something due to us, but as a wondrous gift surpassing both what we deserve and what we dare not ask.

The fifth degree of humility is, not to hide from one’s Abbot any of the evil thoughts that beset one’s heart, or the sins committed in secret, but humbly to confess them. Concerning which the Scripture exhorteth us, saying: “Make known thy way unto the Lord, and hope in Him.” And again: “Confess to the Lord, for He is good, and His mercy endureth for ever.” So also the prophet saith: “I have made known to Thee mine offence, and mine iniquities I have not hidden. I will confess against myself my iniquities to the Lord: and Thou hast forgiven the wickedness of my heart.” (RSB, Chapter 7)

Saint Benedict presents the monk as a sinner so marked by the mercy of God, that he confesses it at every turn. “Confess to the Lord, for He is good, and His mercy endureth for ever” (Psalm 117:1). What is the Divine Office, the Work to which no other work can be preferred, if not the ceaseless confession of the Mercy of God, by day and by night?

And never to despair of God’s mercy. (RSB, Chapter 4)

Finally, Saint Benedict gives us here the one phrase that, to my mind, qualifies him as a Doctor of Divine Mercy: Et de Dei misericordia numquam desperare. “And never to despair of the mercy of God”. In the end, Wilburt, it is this that makes the monk: the perfect child of Saint Benedict is the one who never despairs of the mercy of God. Others may tell you that monastic perfection consists in this observance or that, in the acquisition of virtue, or in the eradication of vice. I shall not contest these affirmations, but I shall place one thing before and after, over and above them all: the perfect monk is the one who stubbornly believes in the mercy of God, “hoping against hope,” even — and especially — when the edifice of his virtues and the ability to carry out every other injunction of the Holy Rule lie in ruins and wreckage all about him.

This is, ultimately, the meaning of becoming a monk. The monk is a man who, again and again, in response to Our Lord’s invitation, freely places himself on the altar, remaining there with the host and with the chalice, in readiness for the invisible descent of Divine Mercy. Once something is placed on the altar, it becomes, Saint Augustine says, sacrificium, a sacrifice made over to God.

God takes whatever a man gives Him in the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. Christ, the Angel of the Father — His Messenger — descends from heaven and, like the eagle in the Canticle of Moses (cf. Deuteronomy 32:11) carries aloft, on the strong and immense wings of His mercy, the offerings set out for the Father upon the altars of His Church. God sends a fire of mercy from heaven to consume those who, binding themselves to Christ, the one spotless Lamb, would pass over into His sacrifice, becoming with Him a pure victim, a holy victim, an immaculate victim giving glory to God and obtaining torrents of mercy for souls.

I know, Wilburt, how much you appreciate the writings of the 24 year old Doctor of the Church, Saint Thérèse of the Child Jesus and of the Holy Face. Her magnificent Offering to Merciful Love expresses, in her own language to be sure, the essence of what a man risks in entering a Benedictine monastery: an unconditional exposure to the Mercy of God, a vertiginous fall into the abyss of the Mercy of God. What is a monk if not a victim cast irretrievably into the holocaust of Merciful Love?

With my blessing,

Father Prior