Saint Antony of the Desert, Father of Monks

Saint Antony and Signor Siciliano

Saint Antony and Signor Siciliano

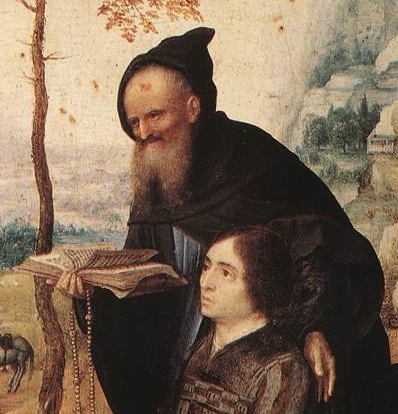

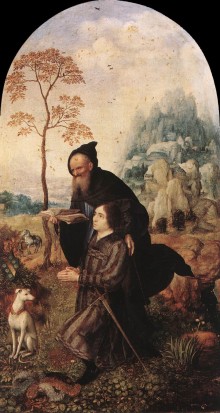

Isn’t this a wonderful painting of Saint Antony? Flemish Jan Gossaert painted it in Rome in 1508 as the right panel of a diptych. The left panel (not shown) depicts the Mother of God. What interests me is the tender spiritual relationship that the artists depicts between Saint Antony and the donor, one Antonio Siciliano.

The Ear of the Heart

Notice the holy abbot’s right hand gently touching Signor Siciliano’s shoulder. In his left hand Saint Antony holds the book of the Scriptures and his prayer beads. Antony’s face is sweet and gentle. Does he not have a lovely smile? His ear is exposed: that ear through which the Word of God entered his mind and descended into his heart.

Precocious Piety

The donor, in contrast, appears sincere, but stiff; he is looking toward the Madonna on the other panel. His rigid piety lacks the seasoned humanity of the old abbot, tried by temptation and marked by compassion. I have known many young men, precociously pious and fascinated by the monastic life, but harsh and rigid in their piety and perfectionism. It takes, sometimes, years — even decades — of humiliating failures and falls before one learns the secret of abandonment to the mercy of Christ that makes one patient, compassionate, and tender. Signor Siciliano’s handsome dog is wearing a stylish red collar. He (or is it she?) is gazing at his master, fascinated by what is going on. Picture yourself in the place of Signor Siciliano. Let the hand of Saint Antony bless and guide you today.

A Certain Primacy Among the Saints

A Certain Primacy Among the Saints

The sacred liturgy makes it clear that Saint Antony of the Desert holds a certain primacy among the saints. The 1970 Missal gives a complete set of proper texts; the reformed Lectionary gives proper readings. (Is there a possibility of mutual enrichment here?) Saint Antony is a primary reference, a model of how we are to hear the Word of God, an inspiration in spiritual combat, a radiant icon of holiness for the ages.

No Rest From Spiritual Combat

The feast of Saint Antony, falling between the Christmas festivities and Septuagesima, is an invitation to shake off the sluggishness that comes with winter, a bracing reminder that there is no rest from spiritual combat, and that “the monk’s life ought at all seasons to bear a Lenten character” (RB 49:1). It is the custom in some monasteries on the feast of Saint Antony to go out to the barn to bless the animals. He is the patron of horses, pigs, cattle, and other domestic animals. Icons of Saint Antony often show his little pet pig nestled in the folds of his tunic. Our little staffie, Hilda, will undoubtedly receive her Saint Antony Day blessing very meekly.

Ice on the Holy Water

Making a trip to the barn in the mid-January cold may be as much of a blessing for the monks as for the animals. It is a wake-up call. One has to use the aspergillum to break the ice that forms on the Holy Water. One sees the animals shudder when the cold water hits them. These are very physical reminders of a spiritual truth. We cannot afford to become cozy and comfortable in a spirituality of feather comforters for the soul. From time to time we, like the barn animals, need the salutary shock of cold Holy Water splashed in our face!

The Life of Antony

The Life of Antony

More than forty years ago dear Trappist Father Marius Granato (+ 10 November 2003) of Spencer introduced me to the Life of Antony by Saint Athanasius. Heady reading for a fifteen year old boy! Shortly thereafter a wise Father told me that one should read the Life of Antony once a year. These seasoned monks knew exactly what they were doing: they were proposing a model of holiness perfectly adapted to the ideals of a youth starting out on the spiritual journey. After all, the Life of Antony begins with an account of his boyhood. He was about “eighteen, or even twenty” when, going into church one day, he heard the Gospel being chanted, and understood that it was Christ speaking to him. “If thou wilt be perfect, go sell what thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven: and come follow me” (Mt 19:21).

A Book For All Ages

A Book For All Ages

Why counsel an annual reading of the Life of Antony? Because it is a text that, in some way, grows with us. If it is suitable for the eager young seeker, it is just as suitable to the Christian wrestling with the oppressive noon-day devil or with the cunning demons of midlife. For the Christian faced with the onset of old age, it is a comforting book. The Life of Antony belongs on the bookshelf of every priest; it should be within the reach of all monks, and even of our Benedictine Oblates.

He Never Looked Gloomy

The portrait of Saint Antony at the end of his life shows a man transfigured: “His face,” says Saint Athanasius, “had a great and marvelous grace. . . . His soul being free of confusion, he held his outer senses also undisturbed, so that from the soul’s joy his face was cheerful as well, and from the movements of the body it was possible to sense and perceive the stable condition of the soul, as it is written, ‘When the heart rejoices, the countenance is cheerful.” Antony . . . was never troubled, his soul being calm, and he never looked gloomy, his mind being joyous” (Life of Antony, 67). This serenity of countenance is what monastic life is supposed to produce!