How the Night-Office is to be said in Summer Time (X)

CHAPTER X. How the Night-Office is to be said in Summer Time

12 Feb. 13 June. 13 Oct.From Easter to the first of November let the same number of Psalms be recited as prescribed above; only that no lessons are to be read from the book, on account of the shortness of the night: but instead of those three lessons let one from the Old Testament be said by heart, followed by a short responsory, and the rest as before laid down; so that never less than twelve Psalms, not counting the third and ninety-fourth, be said at the Night-Office.

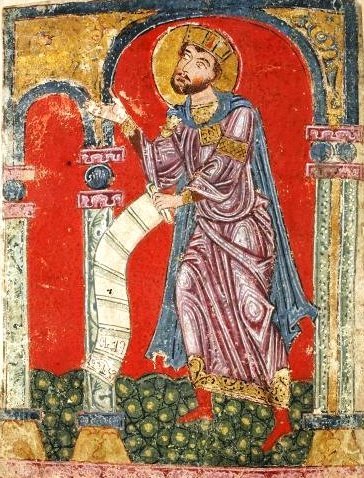

Saint Benedict divides the year into two seasons: summer and winter. Saint Benedict’s summer begins with Holy Pascha and ends on November 1st. After Holy Pascha, the warm season begins in Rome; it is, effectively, the beginning of summer. Winter begins on November 1st with the first bright crisp days that lead up to Martinmas.

Similarly there are two parts to each day; the Romans calculate the day from sunset until sunrise (night), and from sunrise until sunset (day). The day, then, begins with the setting of the sun, even as we begin the greater feasts with First Vespers on the preceding day.

Given that the nights are shorter in summertime, Saint Benedict abbreviates the Night Office during this season in order to begin the Office of Lauds, a celebration of the resurrection of the Lord, with the rising of the sun. The Divine Office is not merely a pondus diei, the paying of a daily debt to the Divine Majesty in a kind of lump sum. Each part of the Divine Office, celebrated at the corresponding hour, has a significance derived from the mysteries of Christ, as Saint Cyprian explains in the text I shared with you two days ago.

In antiquity, the Night Office was a peculiarly monastic prayer, during which monks and virgins, on behalf of the whole Church, kept watch for the advent of the Bridegroom. The Office of Dawn (today called Lauds), in contrast, was, beginning in the fifth century, a daily celebration of the resurrection that attracted the clergy and the people of the great Christian cities. In all of the episcopal cities, the joy of the resurrection resounded in the Morning Office intoned with the rising of the sun. The monks of Antioch, Constantinople, and Milan would have deemed it unthinkable to delay the beginning of the popular Morning Office by prolonging their Night Office past dawn. For this reason, as soon as the first light of dawn began to penetrate the urban basilicas, the monks would end their nocturnal psalmody; straightaway the monks, clergy, and people would begin the solemn Morning Office. This was the prevailing practice in medieval Rome. If, for example, the monks serving in the Lateran basilica miscalculated the length of their Night Office and so found themselves surprised by the glimmers of dawn, they would interrupt the Night Office and intone the Morning Office without delay.

At Monte Cassino, things were different. The monks lived on the mountain height quite apart from any urban centre. They could easily have continued the Night Office past the rising of the sun and then, upon its completion, intoned the Morning Office. Saint Benedict’s Rule was, nonetheless, written for Latin monasteries in various places and circumstances, not excluding the Roman basilical communities. Saint Benedict, therefore, organises the Night Office so that it does not conflict with the Morning Office that drew the populace of Rome into the major basilicas.

The humanity of Saint Benedict—so wise and so discrete—moves him not to advance the hour of the Night Office in order to finish it by dawn but, rather, to replace the three lessons of Sacred Scripture and their responsories with a single short lesson from the Old Testament. Here there is no harsh legalism; this is an example of Saint Benedict’s readiness to adapt even the Opus Dei to local conditions and to the health of the brethren. Blessed Schuster says that there is a morning Collect of the Ambrosian liturgy that praises God for having brought us to light of day post ardorem noctis, “after the heat of the night”. Anyone who has lain awake at night during an Italian summer understands the realism of this Collect. Saint Benedict knows well that the summer heat in Rome can make a good night’s sleep difficult. He prefers to abbreviate the Divine Office in summer to the abbreviation of the sleep of his sons.

It is precisely the moderation and discretion of Saint Benedict in adapting the monastic observance—and even the Divine Office—to changing circumstances and to the infirmities of the brethren that gives to his Rule its universal quality. There are, of course, elements of the observance and of the Divine Office that cannot be changed. These are the supporting columns of Benedictine life, but Saint Benedict limits them and, always, recommends a measure of adaptation in their observance. I am reminded of a sentence in the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy of the Second Vatican Council: “The liturgy is made up of immutable elements divinely instituted, and of elements subject to change” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, art. 21). One of the immutable elements of the Holy Rule is, of course, the recitation of the integral Psalter (all 150 psalms) in the course of a single week. In Chapter XVIII, Saint Benedict will say:

Above all, we recommend that if this arrangement of the Psalms be displeasing to anyone, he should, if he think fit, order it otherwise; taking care in any case that the whole Psalter of a hundred and fifty Psalms be recited every week, and always begun afresh at the Night-Office on Sunday. For those monks would shew themselves very slothful in the divine service who said in the course of a week less than the entire Psalter, with the usual canticles; since we read that our holy fathers resolutely performed in a single day what I pray we tepid monks may achieve in a whole week. (Chapter XVIII)

It is significant that when Saint Benedict is obliged to abbreviate the Night Office in summer time, he does so not by diminishing the number of psalms, but by suppressing the lessons. This demonstrates that for Saint Benedict, as for the whole monastic tradition, the essential obligation of the monk is to the Psalter. The monk, like Yekhiel, the psalm–sayer in Sholem Asch’s magnificent Jewish novel, is the man of the psalms.

His greatest love—the one that brought him most happiness—he reserved for those solitary moments when he clung to God like a child to its mother, merging with Him like a teardrop in the ocean. What brought him to this exalted state was prayer—specifically, reciting Psalms—which asked for nothing more than to be in God’s presence. . . . If the intricate reasoning of Gemara learning was not Yekhiel’s strong point, then tehillim zog’n—Psalm saying—would suffice for bringing him closer to God. (Sholem Asch, The Psalm–Sayer, also titled Salvation, 1934)