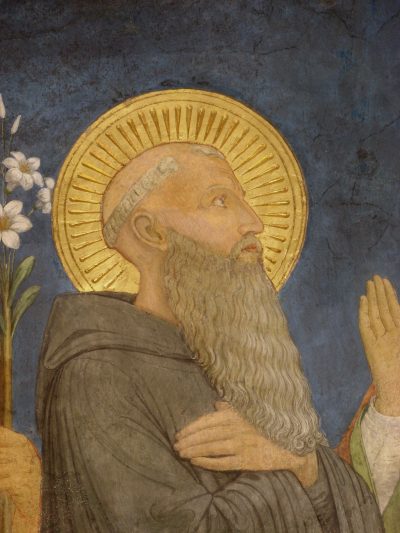

Vir Dei Benedictus

One Desire: To Please God Alone

One Desire: To Please God Alone

Our father Saint Benedict! Saint Gregory resumes in a single phrase our father’s luminous purity of heart: Soli Deo placere desiderans, “Desiring to please God alone”. Herein lies the holiness of Saint Benedict, a man so completely absorbed by the presence of God, so fascinated by the penetrating gaze of God, so attentive to every utterance of God, so consumed with zeal for the ceaseless praise of God, that he withdrew from all else.

The world offered the young Benedict every advantage: learning, prosperity, social prestige, pleasure, power, and possessions. The young Benedict looked the world in the face and, then, walked away from it, never looking back. It was with Benedict as it was with Abraham:

The Lord said to Abram, Leave thy country behind thee, thy kinsfolk, and thy father’s home, and come away into a land I will shew thee. Then I will make a great people of thee; I will bless thee, and make thy name renowned, a name of benediction. (Genesis 12:1–2)

Saint Benedict is a man of one thing only. Saint Benedict shows us what it is to be a monk: vir Dei, a man of God. The life of our father Saint Benedict is the actualisation of the parable of the treasure hidden in the field:

The kingdom of heaven is like a treasure hidden in a field; a man has found it and hidden it again, and now, for the joy it gives him, is going home to sell all that he has and buy that field. (Matthew 13:44)

And again, our father Saint Benedict is like the merchant seeking the finest pearls:

When he had found one pearl of great price, went his way, and sold all that he had, and bought it. (Matthew 13:46)

The monastic vocation of the young Benedict began with the shock of a profound disillusionment with all that the world had to offer. Saint Benedict took the measure of the world around him, and it filled him with disgust. If you, dear sons, would understand why Saint Benedict became a monk, and the father of monks, and if you would probe the grace of your own monastic vocation, return to Psalm 72, and never tire of repeating it to yourselves , especially in moments of temptation:

What bounty God shews, what divine bounty, to the upright, to the pure of heart! Yet I was near losing my foothold, felt the ground sink under my steps, such heart-burning had I at seeing the good fortune of sinners that defy his law; for them, never a pang; healthy and sleek their bodies shew. Not for these to share man’s common lot of trouble; the plagues which afflict human kind still pass them by. (Psalm 72:1–5)

The young Benedict looked at the successful young worldlings around him — the hipsters of the late 5th century — healthy, handsome, well–dressed, successful, rich, and, for all of that, restless and perpetually dissatisfied. “Is this”, he wondered, “all there is to life?” Is there peace in the frenetic pursuit of distraction? Is there joy in the chase after amusements? Again, Psalm 72 describes the young Benedict’s reflection:

I betook myself to God’s sanctuary, and considered, there, what becomes of such men at last. The truth is, thou art making a slippery path for their feet, ready to plunge them in ruin; in a moment they are fallen, in a storm of terrors vanished and gone. (Psalm 72:17–19)

There came a moment of crisis. The young Benedict was at a crossroads. He was compelled to choose.

I was all dumbness, I was all ignorance, standing there like a brute beast in thy presence. Yet ever thou art at my side, ever holdest me by my right hand. Thine to guide me with thy counsel, thine to welcome me into glory at last. What else does heaven hold for me, but thyself? What charm for me has earth, here at thy side? (Psalm 72:12–25)

Forsake the World

There is no monastic life without a radical rejection of the world and all its empty promises. There is no monastic life without a fundamental decision to forsake the world. There is no monastic life without real separation from the world. Looking at our father Saint Benedict, we see that the monk is one who, having heard the message of Saint John the Theologian, takes it to heart, and allows it to determine the course of his life:

Do not bestow your love on the world, and what the world has to offer; the lover of this world has no love of the Father in him. What does the world offer? Only gratification of corrupt nature, gratification of the eye, the empty pomp of living; these things take their being from the world, not from the Father. The world and its gratifications pass away; the man who does God’s will outlives them, for ever. (1 John 2:15–17)

Spiritual Combat

No sooner did Saint Benedict spurn the world and what the world had to offer than he found himself, like Saint Antony and all the Fathers of the Desert before him, in the thick of the struggle that awaits every man who leaves the world: the struggle of combat with his own thoughts of which Saint John Cassian speaks, and with the powers of darkness. There is no monastic life without this struggle, no monastic life without this combat. It is precisely here that, with Saint Paul, a man makes the wondrous discovery of the grace of Jesus Christ.

There was given me a sting of my flesh, an angel of Satan, to buffet me. For which thing thrice I besought the Lord, that it might depart from me. And he said to me: My grace is sufficient for thee: for power is made perfect in infirmity. Gladly therefore will I glory in my infirmities, that the power of Christ may dwell in me. For which cause I please myself in my infirmities, in reproaches, in necessities, in persecutions, in distresses, for Christ. For when I am weak, then am I powerful. (2 Corinthians 12:7–10)

Desire for Heaven

It is this encounter with Jesus Christ, out of a position of infirmity, frailty, distress, and brokenness, that opens a man to the love of Jesus Christ, a love surpassing every other love. It is this that fills a man with desire for heaven, and compels him to live, already on earth, as one raised with Christ into heaven, and hidden with Christ in God.

Risen, then, with Christ, you must lift your thoughts above, where Christ now sits at the right hand of God. You must be heavenly-minded, not earthly-minded; you have undergone death, and your life is hidden away now with Christ in God. (Colossians 3:1–3)

The Love of Christ

And so, Benedict, the man of God became the friend of Christ, a lover of Christ, one for whom the face of Christ, the voice of Christ, the heart of Christ became all his desire and all his joy. It is the love of Christ that runs through the whole Holy Rule, irrigating it with “unspeakable sweetness of love” (Rule, Prologue). In Chapter IV, our father enjoins us “to prefer nothing to the love of Christ”. In Chapter V, he tells us that obedience becomes those “who hold nothing dearer to them than Christ”. And at the end of the Holy Rule, in Chapter LXXII, he exhorts us to “prefer nothing whatever to Christ”. Nothing whatever. No compromise. No half–measures. No holding back.

The Sacred Host

If you would see the substance of what our father Saint Benedict lived and the meaning of how he died, look to the Sacred Host. “This is my body, given up for you” (1 Corinthians 11:24). Given up in leaving the world, because Our Lord Himself says, “I came forth from the Father, and am come into the world: again I leave the world, and I go to the Father” (John 16:28). Given up in triumph over the powers of darkness because He says, “The prince of this world cometh, and in me he hath not any thing.” (John 14:30). Given up in indescribable sweetness because, in the very hour of His death He prays to the Father, saying “That the love wherewith thou hast loved me, may be in them, and I in them” (John 17:26).