Correspondence on the Monastic Vocation 3

Disclaimer: The series of letters entitled “Correspondence on the Monastic Vocation”, while based on the real questions of a number of men in various places and states of life, is entirely fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons, institutions, or places is purely coincidental.

Letter 3: Flynn

Dear Father,

I am a bit confused about what makes a Benedictine . . . well . . . Benedictine. I have been trying to see where God is leading me in my life. I thought I had a Benedictine vocation, and still think that I might, but I need some clarification and some answers. When I first started looking at monasteries, I assumed that all Benedictines would be, more or less, the same everywhere in their outlook and their daily routine. As you know, I’m an American from the Midwest, but I studied in Europe during my last two years of college, and took advantage of the opportunity to visit two or three French abbeys. Unforgettable! I grew up hearing about Chesterville Abbey, St Willibrord’s Abbey, and Spes Nostra Abbey. Every now and then priests from one of these houses would pass through my home parish and supply while the local priest took his vacation or retreat. One of the Fathers from St Willibrord’s was very keen on getting me to go to seminary there, but something made me hold back.

When I was a freshman in college, I went with some guys from the Newman Center to make a retreat with the Trappists at the famous Kidron Abbey. The silence was awesome. The monk who gave a us a few talks in the guesthouse was witty and holy at the same time. I guess that I had already been spoiled by my exposure to the traditional Mass, because the liturgy at Kidron struck me as very stark and low–key. It was reverent but, quite frankly, I found myself hankering after the traditional Latin liturgy the whole time I was there. Some of the guys with me felt the same way, but most of them loved the experience and said they would go back.

I visited Chesterville Abbey and really didn’t like the architecture. I couldn’t imagine spending my life praying in that church 365 days a year! The monks at Spes Nostra Abbey and at St Willibrord’s are wonderful men; there is a Midwestern down–to–earthness about them that I really liked, but I couldn’t get past the English Office and, besides, I don’t feel called to teach or help out in parishes. I never got as far East as St Victor’s Abbey, but I think it must be similar to the places I have visited.

I opened up to Father Philoxenus, the vocation man at St Willibrord’s. He said that the kind of Benedictine life I was looking for did not exist in the U.S. except at Rushbottom Abbey. I went to Rushbottom for a week last summer and was overwhelmed by the beauty of the chant. It was heavenly. I loved the quiet private Masses early in the morning and the solemnity of the Conventual Mass. I wanted it to be for me — I really did! — but deep inside I knew that it wasn’t for me. Talk about feeling confused! I think I need something smaller, just as traditional, but less formal and institutional. Am I making any sense?

It was at this point that I heard about Silverstream Priory. I first wrote to you out of curiosity. To be honest, I never considered Silverstream seriously. It’s in Ireland! I just wanted to know what makes you guys tick. I started reading Vultus Christi, and then I look at the Silverstream webpage and began to follow Silverstream on Facebook. The more I read, the more questions I had. Why, for instance, does Silverstream Priory give such importance to Eucharistic adoration? Is that Benedictine? And there seems to be an amazing devotion to the Blessed Mother at Silverstream. I have never run into these things in other Benedictine houses, not, at least, in the same way. And then, you have this mission to pray for priests. Nothing against it! It’s needed more than ever, from what I can see, but I thought that Benedictines educated men for the priesthood in seminaries. I have never heard of Benedictines who devote their lives to praying for priests. If I understand correctly, Silverstream does not belong to one of the big Benedictine Congregations. Aren’t you under the bishop, or something like that? Sorry for all the questions.

I thought I knew what Benedictines are until I started exploring different monasteries. I have come to the conclusion that no two Benedictine houses are alike. Would you please throw some light on these things for me? I hope to visit Silverstream when I get some time off from the job. Until then, I would appreciate being able to write to you.

Flynn

Dear Flynn,

I understand your confusion about what makes a Benedictine. There are a lot of mixed–messages out there. Sometimes one has the impression that there are as many ways of being a Benedictine as there are monks or, at least, as there are monasteries. I shall try to answer your excellent questions and respond to some of your observations.

First of all, a Benedictine monastery is one in which a stable community, under the authority of an abbot (or prior in a smaller community) live by the Rule of Saint Benedict. This may seem to you as if I am merely stating the obvious. Often, however, in such discussions, it is the obvious that is overlooked. One of my great heroes is the Servant of God Abbot Prosper Guéranger (1805–1875), the restorer of Benedictine life at Solesmes, and the founder of the French Benedictine Congregation. Guéranger began as a priest of the diocese of Le Mans. As a diocesan priest, he had no monastic experience or formal training in Benedictine life. When, in July 1833, he began the restoration of Benedictine life in the priory of Solesmes, he met with sharp criticism from some quarters. “How can Guéranger and his disciples claim to be a Benedictine? They can show no Benedictine pedigree. They are not real Benedictines”. Dom Guéranger answered his critics with a remarkable wisdom and serenity. He simply said, “It is by the Rule of Saint Benedict that we will be Benedictines”. As it was in Guéranger’s 19th century France, so too is it today: “It is by the Rule of Saint Benedict that we will be Benedictines”.

First of all, a Benedictine monastery is one in which a stable community, under the authority of an abbot (or prior in a smaller community) live by the Rule of Saint Benedict. This may seem to you as if I am merely stating the obvious. Often, however, in such discussions, it is the obvious that is overlooked. One of my great heroes is the Servant of God Abbot Prosper Guéranger (1805–1875), the restorer of Benedictine life at Solesmes, and the founder of the French Benedictine Congregation. Guéranger began as a priest of the diocese of Le Mans. As a diocesan priest, he had no monastic experience or formal training in Benedictine life. When, in July 1833, he began the restoration of Benedictine life in the priory of Solesmes, he met with sharp criticism from some quarters. “How can Guéranger and his disciples claim to be a Benedictine? They can show no Benedictine pedigree. They are not real Benedictines”. Dom Guéranger answered his critics with a remarkable wisdom and serenity. He simply said, “It is by the Rule of Saint Benedict that we will be Benedictines”. As it was in Guéranger’s 19th century France, so too is it today: “It is by the Rule of Saint Benedict that we will be Benedictines”.

The Rule of Saint Benedict, like the vast corpus of the writings of the Fathers of the Church, and like the sacred liturgy itself, belongs to no single body holding exclusive rights over it. The Rule of Saint Benedict belongs to the great monastic patrimony of the Undivided Church. Bossuet called the Rule of Saint Benedict “un docte et mystérieux abrégé de toute la doctrine de l’Evangile”, that is, “a learned and mysterious abridgement of the whole doctrine of the Gospel”. Let me translate for you, Flynn, part of Bossuet’s magnificent panegyric on the Holy Rule of Saint Benedict:

Saint Benedict, your blessed legislator, always brings you back to the beginning, judging rightly that the spiritual life cannot subsist without a continual renewal of fervour. It is for this reason that he calls the living out of his rule a little beginning. Let us then speak in truth of this rule; and to crown this humility, by which it was, in so sacred a manner, brought low, let us raise it up today, and celebrate its grandeur and its perfection before the Church of God.

This rule is a summary of Christianity, a learned and mysterious abridgement of the whole doctrine of the Gospel, of all the institutions of the holy Fathers, of all the counsels of perfection. Therein appear with eminence: prudence and simplicity, humility and courage, severity and gentleness, liberty and dependence. Therein correction has all its firmness; condescension, all its charm; commandment, all its vigour; subjection, its repose; silence, its gravity; the word, its grace; strength, its exercise; and weakness, its support: all of this notwithstanding, my Fathers, he [Saint Benedict] calls it a beginning, so as to nurture your always in fear.

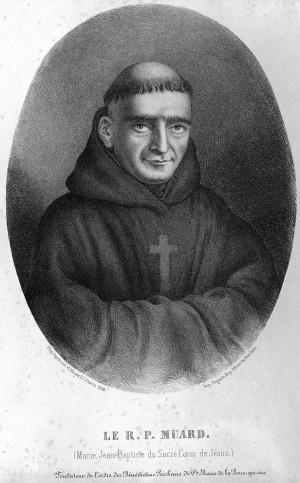

In the 19th century, following the French Revolution and the wholesale devastation of monasic life in Europe, Benedictine life had to be rebuilt from the ground up. It is interesting that the restorers of Benedictine life in that period did not begin as proper monks. They began as secular priests. Their knowledge of monasticism was derived from study and from whatever notions of Benedictine life still remained in the Catholic consciousness. This was the case, not only of Dom Guéranger (1805–1875), the founder of the Congregation of Solesmes, but also of Père Jean–Baptiste Muard (1809–1854), the founder of the Abbey of La–Pierre–Qui–Vire, and of Père Emmanuel André (1826-1903), the founder of the monastery of Le Mesnil–Saint–Loup out of which grew up the French Olivetan Benedictines.

In the 19th century, following the French Revolution and the wholesale devastation of monasic life in Europe, Benedictine life had to be rebuilt from the ground up. It is interesting that the restorers of Benedictine life in that period did not begin as proper monks. They began as secular priests. Their knowledge of monasticism was derived from study and from whatever notions of Benedictine life still remained in the Catholic consciousness. This was the case, not only of Dom Guéranger (1805–1875), the founder of the Congregation of Solesmes, but also of Père Jean–Baptiste Muard (1809–1854), the founder of the Abbey of La–Pierre–Qui–Vire, and of Père Emmanuel André (1826-1903), the founder of the monastery of Le Mesnil–Saint–Loup out of which grew up the French Olivetan Benedictines.

The whole notion of a Benedictine “Order”, understood as a world–wide organisation with a central office in Rome is relatively recent (1893) and, when Pope Leo XIII attempted to bring the Benedictines into line with the centralised model of other Orders, he met with lively resistance among the vast number of Benedictine abbots who held jealously to the principle by which each monastery has the right to exist and develop as an autonomous family. In the end, Pope Leo XIII settled for a union of monastic congregations, (i.e. associations of monasteries organised along national lines or in view of a reform or a missionary endeavour) that nevertheless retain their own autonomy. Today, most, but not all, Benedictine houses belong to a congregation and, by virtue of membership in a congregation, participate in the Benedictine Confederation.

Silverstream Priory does not belong to any congregation; our monastery was erected as a Monastic Institute of Diocesan Right on 25th February 2017. This means that Silverstream is a conventual priory, governed by its own superior and not dependent on any other monastery. All the same, we have close fraternal ties with other Benedictine monasteries and enjoy the encouragement and support of several reigning abbots. Not long ago, the abbot of a flourishing Benedictine house on the continent spent a week with us at Silverstream, sharing fully in our life, and observing us up close. He recognised the authenticity of Benedictine life at Silverstream and testified to it when he returned to his own abbey. In response to the queries of well–meaning sceptics concerning Silverstream’s Benedictine identity, I have always repeated what Dom Guéranger wrote: “It is by the Rule of Saint Benedict that we will be Benedictines”.

Unlike the modern Institutes that arose during the great Catholic Reformation (1545–1648), or even unlike the mendicant Orders that, beginning in the Middle Ages, met the needs of the Church in an organised and effective way, Benedictine monasteries have no pragmatic finality and no particular pastoral project in view. Benedictine monasteries exist only for what Our Lord calls “the One Thing Necessary” (Luke 10:42). Benedictine monasteries provide men with a spiritual family of fathers and brothers who, living permanently in “a place apart” (Mark 6:31), seek God truly in obedience, silence, humility, and unflagging zeal for the corporate liturgical praise of God seven times by day (Psalm 118:164) and once in the night (Psalm 118:62).

This being said, monks must work as well as pray. Monks, furthermore, do not live in a vacuum that isolates them completely from the Church and from her mission to souls. Precisely because Benedictines have no set work or apostolate, they have, down through the ages, been free to respond to the needs of the Church in a variety of ways. Education and scholarship come to mind first. The “Opus Dei” (liturgical service) and “lectio divina” (sacred reading) prescribed by the Holy Rule make teaching and learning indispensable. Benedictine schools, established, first of all, to prepare novices and young monks for the “Opus Dei” and for a lifetime of “lectio divina”, expanded, in many places, to include education of the diocesan clergy. Not surprisingly, the circle widened even more to include the education of boys and young men destined neither for the cloister nor for the diocesan clergy. Here in Ireland, for example, the Benedictine monks of Glenstal Abbey in County Limerick conduct a school renowned for its academic excellence.

Every monastery is marked by the events and circumstances surrounding its birth. Silverstream Priory came into existence during the pontificate of Pope Benedict XVI. Our very being as a community is strongly marked by the grace of that most Benedictine of pontificates. The Year of the Eucharist (2004–2005), inaugurated by Saint John Paul II and concluded by Pope Benedict XVI, and the Year of the Priesthood (2009–2010) promulgated by Pope Benedict XVI were defining moments for our monastery. Pope Benedict XVI’s Motu Proprio “Summorum Pontificum” expressed and confirmed our understanding and practice of the sacred liturgy in its traditional form. It was clear, from the very beginning, that we would be characterised by adoration of the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar; by a fatherly and fraternal solicitude for priests labouring in the vineyard of the Lord; and by the fresh liturgical impetus of “Summorum Pontificum”. What Pope Benedict XVI wrote concerning Pope Saint Gregory the Great is fittingly applied to himself:

He greatly encouraged those monks and nuns who, following the Rule of Saint Benedict, everywhere proclaimed the Gospel and illustrated by their lives the salutary provision of the Rule that “nothing is to be preferred to the work of God.”

Pope Benedict XVI wrote of “those monks and nuns who, following the Rule of Saint Benedict, everywhere proclaimed the Gospel”. While not all missionaries are monks, all monks are missionaries. Does this surprise you, Flynn? Every Benedictine monastery has a missionary vocation because every Benedictine monastery is an outpost and an inbreaking of the Kingdom of God. Monks evangelise, above all, by demonstrating the absolute primacy of God.

Flynn, you wrote so many questions in your letter, that I will have to devote another whole letter to answering them. In the meantime, know that I keep you in my prayer. I hope that what I have shared with you thus far will serve to clarify the things about us (and all Benedictines) that you find puzzling.

Father Prior