The Heart of the Rule: the Healing of Hearts

In our thrice-a-year cycle of Reading the Holy Rule of Saint Benedict, we begin today reading Chapter 7 On Humility. This chapter is often called the heart of the Rule since it is the core of Saint Benedict’s spiritual doctrine leading to the “perfect love of God which casts out fear” (RSB 7; cf 1 John 4:18). Why is Humility, of all the virtues, treated not just as one virtue among many, but as the heart of Saint Benedict’s spirituality?

The Seeking of God: the Highest Good

A man comes to the monastery to “seek God” (RSB 58). In order to seek God, he must “return by the labour of obedience to Him” from Whom he has “departed by the idleness of disobedience” (RSB Prologue) One must ask, why, at the deepest level, does the monk seek God? The answer is a very human one, because God has built it into the deepest parts of human nature itself: we seek God above all because God is Good. God is Goodness in Itself, and the Creator of all and the Source of Goodness in all. Saint Thomas Aquinas describes this beautifully in an unlikely place. At the beginning of His Catena Aurea on Mark (his commentary on the Gospels based on the words of the Church Fathers), he writes the following in his dedication preface:

God, the maker of everything, by a simple glance of his goodness, brought everything into being, and endowed all creatures with a natural love of goodness. Thus, as each thing naturally loves and desires the good that befits it, it displays a wonderful turn about and pursuit of its author.

All creatures must love goodness because goodness consists in a thing being in some way desirable. Anything is desirable insofar as it is perfect, and it is perfect insofar as it is actual. Thus being, which is actuality, is in what goodness consists (I, q.5, a.1). What then is the ultimate Good, but the Actus Purus? The Pure Act, Pure Being. There can be no greater good than He Who is Being itself. (Cf. I. q.6 a.2) Thus, if a monk wishes to pursue the good, which he does by nature, then he must seek God, the source of good.

The Problem of Evil

In the beginning of his Summa Theologiae, Saint Thomas Aquinas responds to what is commonly known as the “Problem of Evil”. In his article on “Whether God Exists” the first objection raised is the following:

It seems that God does not exist; because if one of two contraries be infinite, the other would be altogether destroyed. But the word “God” means that He is infinite goodness. If, therefore, God existed, there would be no evil discoverable; but there is evil in the world. Therefore God does not exist. (I. q.2, a.3, obj 1)

In other words, as many atheists say, If God is infinitely Good, how can there be any evil in the world? It is not a new question, and the answer is not new either:

As Augustine says (Enchiridion xi): Since God is the highest good, He would not allow any evil to exist in His works, unless His omnipotence and goodness were such as to bring good even out of evil. (bene faceret etiam de malo). This is part of the infinite goodness of God, that He should allow evil to exist, and out of it produce good. (ibid, ad 1)

God, Who is infinitely Good, allows evil to bring good out of it. In the beginning of Genesis He created ex nihilo (from nothing); throughout the rest of salvation history He does better than creating ex nihilo: He creates etiam de malo (even from evil).

At first, however, there seems to be a problem, as Saint Thomas appears to avoid the objection as stated. The objection isn’t why God allows evil but why it can exist at all. It would seem that God, Who is infinitely good, per se should “cancel out” evil immediately. The reason Saint Thomas doesn’t respond directly to this is because the solution might have seemed to him too obvious to say explicitly: there is no pure evil. There cannot be pure evil so long as there is any being at all. That God exists, that anything exists at all, means that evil in an absolute sense is in fact altogether “destroyed”.

What we are left with then is the lesson we are to take away from Saint Thomas’ response. The only evil that exists is mixed evils, that is, good things with a greater or lesser privation of good as God permits. And as Saint Thomas says, quoting Saint Augustine, God permits this precisely in order to bring good out of it, etiam de malo.

The Problem of Me

Where does this leave the monk?

Unfortunately, the man seeking God finds himself affected by sin. Human beings, existing in the material world, are contingent and corruptible. Any creature that exists is less than God and therefore subject to becoming a mixed evil. And thanks to original sin, everyone finds himself already corrupted in this way. Thus, as Saint Benedict has reminded us in the Prologue, we have departed from God by disobedience.

But the Good News is that He also provides the remedy. As we have discovered, God permits all of these mixed evils precisely because He wants to create a good etiam de malo: etiam de me (even from me!).

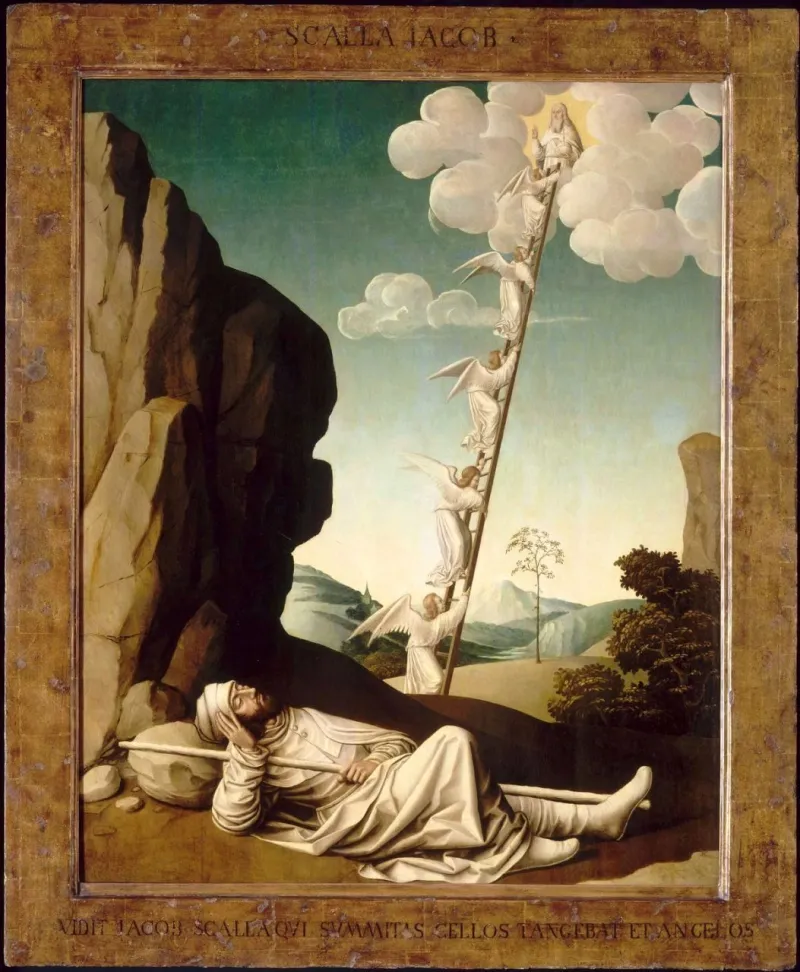

Jacob’s Ladder

Saint Benedict describes the core of this problem and its remedy in Chapter 7 which we are reading today. He speaks of erecting a ladder with the degrees of humility by which the monk ascends to God. He makes reference to the vision of the ladder that the Patriarch Jacob saw in a vision:

And he came to a certain place, and stayed there that night, because the sun had set. Taking one of the stones of the place, he put it under his head and lay down in that place to sleep. And he dreamed that there was a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven; and behold, the angels of God were ascending and descending on it! (Gen 28:11-12 RSVCE)

Biblical scholars like to debate whether what Jacob saw in the dream was a ladder or a staircase, or some other elevatory apparatus. In reading Saint Benedict, it is very important to note that he chose to stick with the Vulgate tradition and refer to it as the Ladder.

The Ladder of Humility

Here is what Saint Benedict says about the ladder just before going into his description of each degree:

Without doubt, this descent and ascent can signify only that we descend by exaltation and ascend by humility. Now the ladder erected is our life on earth, and if we humble our hearts the Lord will raise it to heaven. We may call our body and soul the sides of this ladder, into which our divine vocation has fitted the various steps of humility and discipline as we ascend. (RSB 7:6-9)

It is obvious that the rungs of the ladder, being the degrees of humility, are how we ascend toward God (and the same could be true of a staircase), but Saint Benedict is, at the same time, saying something else about this ladder that is easily missed. If the “sides” of the ladder are the “body and soul”, then even before we ascend the rungs, they do something much more fundamental: they connect the body and soul back together.

The human condition since the fall is such that there is an apparent disjunct between the body and the highest parts of the human soul. They are like two sides of a ladder which are parallel; left to himself, man is not fully unified, and he cannot ascend to God. Due to concupiscence, the intellect and will no longer have full control over the lower faculties, and so this appears as a disunity in the human person.

In short, if a monk has departed from his Creator by pride, it is because he is not living in reality. His mind is off wherever it would want to go with its delusions of grandeur; meanwhile, his body is overcome by passions and tends to act like a brute animal. The rupture between the body and soul lies in the human heart.

The “Stitches” of Humility

Humility is the solution to the problem: it allows us to ascend to God on its rungs, but it does so first of all because it connects our body and soul back together, stitching back together, if you will, that rupture of the heart. Humility simply is the path through which a monk is brought to live in reality. By obedience, by manual labour, by confession of faults, the monk is confronted with his own existence in the world. He begins to see the whole world as a sacramental that points back to its Creator. As his own disunity is repaired, his advance in perfection is brought about by the Source of all perfection Who governs things toward their end.

In this the monk working toward the conversion of his own soul sees the solution to the problem of evil first in himself and then in others. Evil as a privation of good is a lack of being. All being, every being qua being, is good. If there is anything or anyone that is evil in any way, it is because it is a contingent being which is not fully actualised. God Who is the Source of all goodness and Who directs all things to their end has allowed it to exist in a state of privation. And thus is the process of conversion a participating in God’s creation of Good out of evil.

To Climb, but First to Heal

As we spend the next two weeks listening to the Degrees of Humility that our Holy Father Benedict lays out for us, let us not seek to climb in great strides with the ardour of strength, but let us first allow the Divine Physician to mend the wound of sin in each of our hearts, allow Him to stitch our very nature back together by the humility which leads to “obedience unto death” (Phil 2:8). The Son is the Doctor of Souls, and His prescription is the Holy Rule.

The End of Christmas

Today also marks the beginning of the novena to the Feast of the Presentation of Our Lord in the Temple (also known as the Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary or Candlemas), the final peak in the foothills of Christmastide. As we prepare for that great Feast, we may meditate on the Epistle of its Mass from the Prophet Malachi, which lays out our Lord’s work in our souls, leading to a life of adoration and reparation:

For He is like the refiner’s fire, or like the fuller’s lye. He will sit refining and purifying silver, and He will purify the sons of Levi, refining them like gold or like silver that they may offer due sacrifice to the Lord. Then the sacrifice of Juda and Jerusalem will please the Lord, as in the days of old, as in years gone by, says the Lord almighty. (Mal 3:2-4)