The Monastery: A Hospital for the Sick

Blessed Cardinal Schuster On Discretion in Commanding

Holy Rule, Chapter 2, Section 5: 13 January/14 May/13 September

1. ‘The Abbot in his government should be inspired always by the direction of the Apostle Paul, who wrote to Timothy: “Reprove, entreat, rebuke.”‘Let them therefore alterrnate his criteria with the times, enticements with threats; after the austere love of the master, let him show the loving affection of the father.

‘Let him therefore show himself firm with undisciplined and restless characters; on the other hand, let him stimulate the obedient, the meek, and the patient to do even more.

‘We desire absolutely that the abbot reprove and rebuke the negligent and the heedless, without in any way dissimulating the faults of the guilty; nay rather, as soon as the evil grasses begin to sprout, let him pull out their very roots as best he can, dreading the unhappy lot of Eli, priest of Silo.’

***

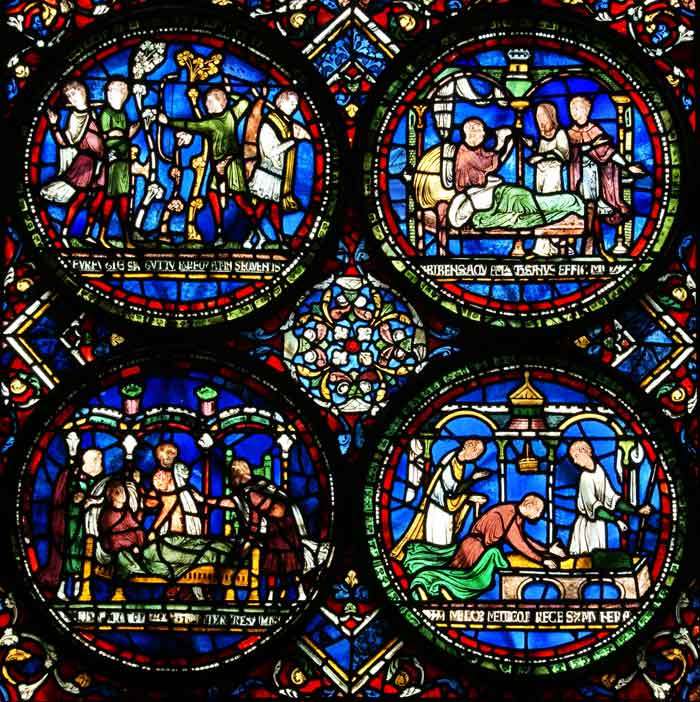

2. According to the Cassinese Patriarch, the monastery can be compared to a sort of clinic, where one enters to be healed of spiritual maladies, the consequence of original sin.

As the theologians enumerate a full seven capital vices, so the spiritual diseases are numerous, and should be cured each one with its own method. One sole standard of care and one identical medicine would easily kill the sick, rather than curing them.

Saint Benedict desires, therefore, that the Abbot distinguish times, temperaments, and methods of care.

If the abbot shows himself too strong with one who is already timid or prone to melancholy, he will easily dishearten him beyond remedy. If, on the other hand, he shows himself too weak with the arrogant, they will take new courage, and will believe that they can obtain everything in the monastery ‘by not making themselves sheep.’

Saint Francis de Sales too explains the same thing, observing that, in front of the wolf and the arrogant man, if even the shepherd makes himself a sheep, the enemy will easily do with the flock what he wills.

If, therefore, there is in the community some type who likes to conduct himself more as a wolf than as a sheep, he should know well that the monastery is not his place: he should either change himself, or change sheepfold.

***

3. Saint Benedict sets forth in this chapter an important page of psychology and of spiritual direction.

The time is not always the same, since the year itself has a full four seasons. So is it also with the life of the soul. Times of aridity succeed to times of fervour, days of temptation to days of peace, periods of darkness to weeks of light.

The spiritual director must take account of all these vicissitudes, adapting his counsels to the different states of the disciple. But the Abbot, Saint Benedict continues, should not comport himself towards the monks solely as a mamma. He should above all be their master and father, who indeed always loves them, but who employs diverse means to express his own heart.

The affection of the master, in the Roman mentality, should be dirum. We would say simply: austere.

May God nonetheless deliver us from superiors who govern only with the head, as professors or as Cato the censor.

It is necessary to temper the intelligence with the heart; and for this reason the Holy Patriarch adds: pium patris ostendat affectum. (Rule, Chapter 2: ‘Let him show the father’s tender affection.’)

Several times Saint Gregory the Great describes to us episodes in which Saint Benedict demonstrates this fatherly compassion towards certain failings of the disciples.

Once, he performs a miracle to come to the aid of the Goth who had let his work tool end up in the lake, and he tells him: Ecce labora et noli contristari. ‘Here it is: now go back to work, and do not be distressed anymore!’ (St Gregory, Dialogues, Book II, Chapter 6)