How Solicitous the Abbot Should Be of the Excommunicate (XXVII)

CHAPTER XXVII. How Solicitous the Abbot Should Be of the Excommunicate

4 Mar. 4 July. 3 Nov.

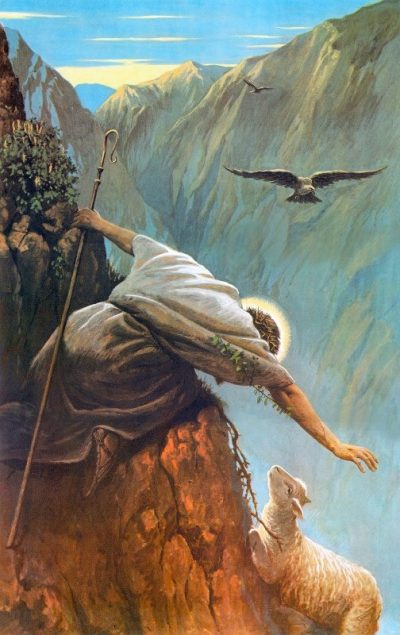

Let the Abbot exercise all diligence in his care for erring brethen, for they that are in health need not a physician, but they that are sick. He ought, therefore, as a wise physician, to use every remedy in his power. Let him send senpectae, that is old and prudent brethren, who may as it were secretly comfort the troubled brother, inducing him to make humble satisfaction and consoling him, lest he be swallowed up with overmuch sorrow. Let charity be strengthened towards him, and let everyone pray for him. For the Abbot is bound to use the greatest care, and to exercise all prudence and diligence, so that he may not lose any of the sheep entrusted to him. Let him know that what he has undertaken is the charge of weakly souls, and not a tyranny over the strong; and let him fear the threat of the prophet, wherein God saith: What you saw to be fat, that ye took to yourselves: and what was feeble, ye cast away. And let him imitate the merciful example of the Good Shepherd, who left the ninety and nine sheep in the mountains and went after the one sheep that had strayed; and had so great pity on its weakness, that he deigned to place it on his own sacred shoulders and so bring it back to the flock.

Rarely does God call men of dazzling qualities, spotless integrity, and perfect health to the monastic life. A monastery is not a stadium for ascetical performances; it is an infirmary for souls in various stages of spiritual convalescence and recovery. Saint Benedict confirms this in Chapter LXXII, where he says, “Let them most patiently endure one another’s infirmities, whether of body or of mind.” And in today’s Chapter, Saint Benedict says, “Let him [the Abbot] know that what he has undertaken is the charge of weakly souls.” God does not see as men see. Where men read failure, crisis, and instability, God reads scope for the deployment of His mercy, His power, and His faithfulness.

“Jesus saith to them: Have you never read in the Scriptures: The stone which the builders rejected, the same is become the head of the corner? By the Lord this has been done; and it is wonderful in our eyes” (Matthew 21:42). The master-plan of the Father by which the Son, rejected by the builders of this age, became the head of the corner in the building of the Kingdom of God, is continued through the ages in the saints, known and unknown, in the lives of those canonized by the Church and in the obscurity of lives totally unknown to men. It pleases God to make use of those whom the wise and clever reject. God is forever salvaging men from the scrap-heap of unsuitables to which the world (and the worldly in the Church) have consigned them.

I reflected have much on Our Lord’s choice of Saints Peter and Paul as the very foundations and pillars of His Church. When Our Lord called Simon Peter, He knew in advance that Peter would prove to be a cracked and unreliable element in the foundation of His Church. He knew that Peter would deny Him. He knew that Peter would show more cowardice than courage in the face of suffering. He also knew that, after the Resurrection, a fallen Peter would make this splendid confession of confidence and of love, this perfect act of reparation: “Lord, thou knowest all things: thou knowest that I love thee” (John 21:17).

When Our Lord called Saul of Tarsus, He saw a man marked by pride, spiritually arrogant, excessive in word and in deed, sunk deep in self-righteousness, and tormented by an inward unrest. He also saw Paul the Apostle, profoundly humble, with entrails of mercy for sinners and compassion for the weakest among men, capable of great heroism in the service of the Gospel, totally abandoned to His all-sufficient grace, and capable of radiating the peace of the Holy Ghost.

See your vocation, brethren, that there are not many wise according to the flesh, not many mighty, not many noble: But the foolish things of the world hath God chosen, that he may confound the wise; and the weak things of the world hath God chosen, that he may confound the strong. And the base things of the world, and the things that are contemptible, hath God chosen, and things that are not, that he might bring to nought things that are: That no flesh should glory in his sight. But of him are you in Christ Jesus, who of God is made unto us wisdom, and justice, and sanctification, and redemption: That, as it is written: He that glorieth, may glory in the Lord. (1 Corinthians 1:26-31)

An Abbot must accept the family of flawed and broken men that God has entrusted to him, fearing the threat of the prophet, wherein God saith: What you saw to be fat, that ye took to yourselves: and what was feeble, ye cast away. This is not to say that all comers are to be taken in. Vocations must be studied carefully; some men will have to be sent away as being unsuited to the claustral life. Belief in the power of grace and reliance on the healing work of the Holy Ghost do not dispense one from exercising common sense, prudence, and due diligence.

This being said, once a man has been adopted into the monastic family by profession, he is to treated as a son of the household. By the vow of stability a monk binds himself to a particular monastic family, to its father, and to his brothers. After simple profession, the new relationship is recognized and affirmed; and the decision to go forward is made public. With solemn profession, the adoption is complete.

A monastery is not a business in which employees can be fired on grounds of unsuitable performance. It is not a university from which those who prove to be dullards can be dismissed. It is not an exclusive club denying full membership to those lacking the desirable prerequisites. A monastery is a family, utterly dysfunctional by any human standards and, at the same time, functioning by grace as a living organism of the Body of Christ.

Other religious Orders can reject, and rightly, men lacking in the qualities and talents needed for their specialized or characteristic apostolates. A Jesuit needs a quick brain, a readiness for abnegation, and the ability to move comfortably in the world without becoming worldly. A Dominican has to be able to preach and to demonstrate the splendour of the truth, praising God all the while. A Franciscan has to be able to live on very little, in the total renunciation of ownership, and in a joyful and carefree abandonment to Providence. A Redemptorist has to be able to evangelise the poor in the remotest places, using a language that is simple and capable of touching the heart.

We Benedictines have no distinctive apostolate, no specialized ministry, no specific goal except ceaseless prayer and purity of heart. In Chapter LVIII of the Holy Rule, Saint Benedict requires but three things of a man seeking admission to the monastery: 1) that he truly be seeking God; 2) that he be zealous for the Divine Office; 3) that he embrace obedience and humiliations readily. In men having these three requisites, an abbot will find sons ready for adoption into the monastic family. If any one of the three requisites are missing, a man cannot be said to have a Benedictine vocation.

While it is true that monasteries may undertake certain works, those works do not define the monastic life. When the works undertaken by Benedictines fail, or go bankrupt, or are suppressed by a hostile government, nothing of the essence of Benedictine life is affected. Monks are not about making jellies, or cheese, or fruitcakes, or beer, though they may do all of these things, and do them very well. Monks are not about designing vestments and sewing them, or about writing icons, or about writing learned treatises, or about running excellent schools, though they may do all these things and make a success of them. Monks are not even about singing Gregorian Chant, although one might dare hope they do, and do it well!

All of this is by way of background to Chapter XXVII. It is, to my mind, one of the most beautiful Chapters of the Rule; it reveals Saint Benedict’s paternal heart. The Abbot is a physician dedicated to the care of sin-sick souls; he is a father concerned lest any one of his sons fall into too great a sadness; he is a Good Shepherd, ready to pursue the one sheep gone astray, to take pity on its weakness, and to carry it on his own shoulders over terrains that are rough and treacherous The duty of the Abbot is to keep his family together, holding as strongly and as tenderly to the feeble and fragile as to the healthy and strong.

A most beautiful and inspiring reflection on the path to healing our wounded natures, thank you.