Rejoicing may this day go hence

CHAPTER XIII. How Lauds Are to be Said on Weekdays

CHAPTER XIII. How Lauds Are to be Said on Weekdays

15 Feb. 16 June. 16 Oct.

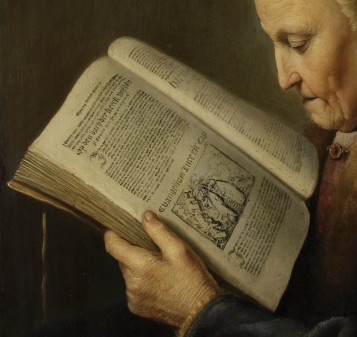

On week-days let Lauds be celebrated in the manner following. Let the sixty-sixth Psalm be said without an antiphon, as on Sundays, and somewhat slowly, in order that all may be in time for the fiftieth, which is to be said with an antiphon. After this let two other Psalms be said according to custom; that is, on Monday, the fifth and thirty-fifth: on Tuesday, the forty-second and fifty-sixth: on Wednesday, the sixty-third and sixty-fourth: on Thursday, the eighty-seventh and eighty-ninth: on Friday, the seventy-fifth and ninety-first: and on Saturday, the hundred and forty-second and the Canticle from Deuteronomy, which must be divided into two Glorias. But on the other days let canticles from the prophets be said, each on its proper day, according to the practice of the Roman Church. Then let the Psalms of praise follow, and after them a lesson from the Apostle, to be said by heart, a responsory, a hymn, a versicle, a canticle out of the Gospel, the Litany, and so conclude.

Psalm 66

Having already established the pattern of Lauds for Sundays, Saint Benedict here has only to order the details that pertain to its celebration on weekdays. Psalm 66 (see my commentary in the preceding post) is said as on Sundays. Saint Benedict, knowing human frailty and providing for it even within the liturgy, would have Psalm 66 be chanted “somewhat slowly” so that the laggards and dawdlers in the community might be in their places in choir in time for Psalm 50, the Miserere. This is a characteristically Benedictine detail; it shows Saint Benedict’s provision for human weakness. Saint Benedict knows that in every community there will be laggards and dawdlers. Astonishingly, he accommodates them . . . to a point.

Benedictine Realism

In this paternal provision for the imperfect, the less-than-zealous, and the plodder, we see one of the characteristic traits that distinguish Benedictine asceticism from other schools of perfection. Saint Benedict assumes that wheresoever men are living together one will find the usual array of little miseries and weaknesses that affect fallen human nature. Saint Benedict does not have recourse to rigidity. Rather than tighten the controls, he provides a way of integrating such weaknesses harmoniously into the rhythm of daily life and, even, into the Work of God.

Short Lesson or Capitulum

As on Sunday, after the Laudate Psalms (148-149-150) there is a short lesson from Saint Paul, such as this one:

It is now the hour for us to rise from sleep. For now our salvation is nearer than when we believed. The night is passed, and the day is at hand. Let us therefore cast off the works of darkness, and put on the armour of light. Let us walk honestly, as in the day. (Romans 13:11-13)

Responsory

A responsory follows the short lesson. The 17th century Maurists were brilliant at the composition of responsories for their breviary. Each lesson had a responsory perfectly assorted to it. Here is an example of a responsory to the lesson above, composed in the Maurist fashion.

R. Thou hast made the morning light and the sun. (Psalm 73:16) * To thee do I watch at break of day. (Psalm 62:1). V. I rose up and am still with thee.(Psalm 138:18) R. To thee do I watch at break of day. V. Glory be to the Father and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost. R. Thou hast made the morning light and the sun. * To thee do I watch at break of day.

Hymn

Saint Benedict does not exclude hymns from the Opus Dei; his preference goes to those attributed to Saint Ambrose (340-397). My favourite hymn at Lauds is the one given for Monday. The translation is by poet laureate Robert S. Bridges (1844-1930):

O splendor of God’s glory bright,

O Thou that bringest light from light;

O Light of light, light’s living spring,

O day, all days illumining.

O Thou true Sun, on us Thy glance

Let fall in royal radiance;

The Spirit’s sanctifying beam

Upon our earthly senses stream.

The Father, too, our prayers implore,

Father of glory evermore;

The Father of all grace and might,

To banish sin from our delight.

To guide whate’er we nobly do,

With love all envy to subdue;

To make ill fortune turn to fair,

And give us grace our wrongs to bear.

Our mind be in His keeping placed

Our body true to Him and chaste,

Where only faith her fire shall feed,

To burn the tares of Satan’s seed.

And Christ to us for food shall be,

From Him our drink that welleth free,

The Spirit’s wine, that maketh whole,

And, mocking not, exalts the soul.

Rejoicing may this day go hence;

Like virgin dawn our innocence,

Like fiery noon our faith appear,

Nor known the gloom of twilight drear.

Morn in her rosy car is borne;

Let Him come forth our perfect morn,

The Word in God the Father one,

The Father perfect in the Son.

All laud to God the Father be;

All praise, eternal Son, to Thee;

All glory, as is ever meet,

To God the holy Paraclete.

Versicle

The versicle that follows is graced in the sung Office with a lovely little melism (vocal adornment) on the last syllable:

V. We are filled in the morning with thy mercy.

R. And we have rejoiced, and are delighted all our days. (Psalm 89:14)

The Benedictus

The Benedictus or Canticle of Zacharias (Luke 1:68-79) follows. It is the high point of Lauds, a solemn praise of the Christ the Orient (the rising sun) that visits us from on high to guide our feet into the way of peace. Although Saint Benedict does not mention it, an antiphon probably accompanied the chant of the Benedictus in his day, just as it does in the Office in use today.

Blessed be the Lord God of Israel;

because he hath visited and wrought the redemption of his people:

And hath raised up an horn of salvation to us,

in the house of David his servant:

As he spoke by the mouth of his holy prophets,

who are from the beginning:

Salvation from our enemies,

and from the hand of all that hate us:

To perform mercy to our fathers,

and to remember his holy testament,

The oath, which he swore to Abraham our father,

that he would grant to us,

That being delivered from the hand of our enemies,

we may serve him without fear,

In holiness and justice before him, all our days.

And thou, child, shalt be called the prophet of the Highest:

for thou shalt go before the face of the Lord to prepare his ways:

To give knowledge of salvation to his people,

unto the remission of their sins:

Through the bowels of the mercy of our God,

in which the Orient from on high hath visited us:

To enlighten them that sit in darkness, and in the shadow of death:

to direct our feet into the way of peace.

The Litany

Saint Benedict begins the conclusion of Lauds with the Litany, that is, “Lord, have mercy upon us. Christ, have mercy upon us. Lord, have mercy upon us.” Even this short formula (Kyrie eleison, Christe eleison, Kyrie eleison, in Greek) is, in effect, an offering of praise to Christ, the victorious King, who dispenses the divine alms of His mercy to souls that cry out to Him.