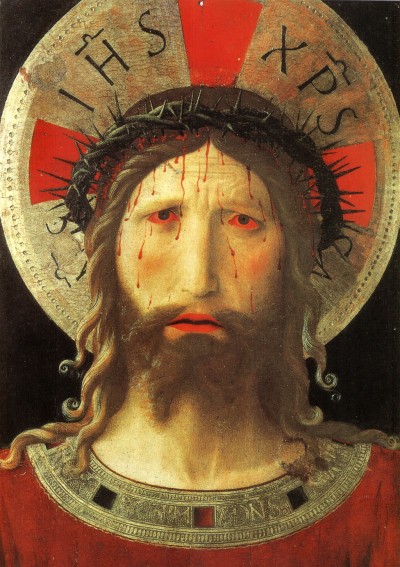

The Crown of Thorns and Mental Illness

Union with the Passion of Christ

Union with the Passion of Christ

The sacred liturgy provides man with the divinely inspired means to express his need in every situation, affliction, infirmity, and distress. If this is true at all times, it is especially true in the liturgy of Lent. The Propers of the Lenten Masses together with the antiphons and responsories of the Divine Office provide all who suffer with the means to lift their minds and hearts to God while uniting their afflictions to the Passion of Christ.

The Feast of the Sacred Crown of Thorns

The devotional feast of the Sacred Crown of Thorns is a case in point. The feast in honour of the Crown of the Lord (Festum susceptionis coronae Domini) was instituted at Paris when, in 1239, Saint Louis IX of France received the relic of the Crown of Thorns. The sacred relic of the Crown was later enshrined in the Sainte Chapelle together with other precious relics of the Passion. The feast, observed on 11 August in the Sainte Chapelle came, over time, to be celebrated in other places in France.

In the following century another festival of the Sacred Crown appeared in parts of Spain, Germany, and Scandinavia on May 4th, and was celebrated in conjunction with the Feast of the Invention of the Holy Cross. The Dominicans, until recently, kept the feast with a magnificent proper Office on April 24th.

Pope Clement X (1676) and Pope Innocent XI (1689) granted the diocese of Freising in Bavaria a special feast of the Sacred Crown of Thorns on the Monday after Passion Sunday. At Venice in 1766 the feast was kept on the second Friday of March and in 1831 it was adopted at Rome as a double major to be kept on the Friday following Ash Wednesday.

Mental Illness Is Not an Impediment to Holiness

Blessed Mother Teresa of Calcutta is reported to have said that the Crown of Thorns is the emblem of all who suffer from depression, anxiety, or any form of mental illness. Mother Teresa’s observation gives a particular relevance to today’s feast. One hears of saints who suffered from all sorts of physical maladies. Rarely does one hear of saints who suffered mental illness, but they do exist and probably in a much greater number than one would think. The classic reference is, of course, Saint Benedict Joseph Labre who has been variously diagnosed as a social misfit, an eccentric, and even a schizophrenic, but there are many others. I think of the hypersensitive Saint Thérèse who, in her childhood, suffered from “nerves” and, in her final illness, struggled against the temptation to despair. I think of her father, Saint Louis Martin, who was committed to the Bon Sauveur asylum for the mentally ill in Caen, and of her sister Léonie who, after enduring abuse from a family servant, was emotionally fragile all her life. Mental and emotional illness are not an impediment to holiness.

Each Man His Crown of Thorns

I see the liturgical commemoration of the Sacred Crown of Thorns as the patronal festival of all who live with mental illness, or struggle with depression, or are paralysed by anxiety, or in the grip of a compulsion, or bound up in some vice, or tormented by scrupulosity. Just as Julien Green said that each man has his own night, I would say that each man wears his own crown of thorns.

Mental Health and Holiness

Many years ago I read an article * of Father Louis Beirnaert, S.J. that was originally published in the Revue Études in 1950. The article marked me when I first read it and its message of hope has remained with me. In honour of today’s feast of the Crown of Thorns, I decided to translate some excerpts from Father Beirnaert’s article.

There are [individuals with] unlovely psyches, poor in natural dispositions for a life in conformity with the moral law: they are those beings who will never be fully virtuous and who will drag themselves from weakness to weakness until the end of their life; there are [individuals with] dry and irreducibly rationalistic psyches who will never have any appreciation for the sacraments and for a simple submission to the mystery; there are infantile psyches, haunted by the need for security, obsessed by a false culpability; there are individuals with so many psychological abnormalities, great or small, that they will never be capable of lucid judgments of value and consistency of will. Are all of these — and they are numerous — really disadvantaged when it comes to holiness?

Make no mistake about it: it is as hard for a poor wretch to consent to being saved by the Other as it is for an individual shining with virtue to recognise humbly that God has done everything in him. The psychologically rich individual will be tempted to the end of his life to be complacent in his qualities; the psychologically poor individual will tempted to the end of his life to revolt or to make a display even of his misery. The one like the other must go through the same death . . . because for the one as for the other, it will come, in the end, to the same renunciation of pride and self–sufficiency.

There are saints with unattractive and difficult psychological profiles: the troop of the anguished, aggressive, and flesh–bound, driven by the unbearable weight of their compulsions. There are ” born failures” whose heart will never be anything but a nest of vipers, unfortunate persons with an unattractive face, boys who could never identify with their father. There are saints who will never charm the birds or caress the wolf of Gubbio. There are those who fall and who will fall again and again. There are those who will shed tears right up to the end, not because they slammed a door a little too energetically, but because they are still committing a sordid unavowable fault. There is the immense crowd of those whose sanctity here below will never glow with mental health, and who will have to wait for the last day to shine in perpetuas aeternitates. These are saints without having the name.

Next to these, there are the saints with a happy psychological profile: saints chaste, and strong, and gentle — model saints — canonised or canonisable. Their unfettered heart is as expansive as the sands along the sea, quasi arenam quae est in litore maris. Their mental health sings the glory of God like a well–tuned harp. These are the admirable saints who inspire thanksgiving and in whom we touch a humanity transformed by grace. These are the recognised saints, those whose feasts we keep, the great saints who have left a trace of light in history.

These two types of saints are [nonetheless] brothers. Saint Teresa [of Avila] and Saint Ignatius, with their robust character, are closer to Graham Green’s “whisky–priest” than to the man radiant with mental health or with a moral conformism that was never shaken to its roots, and who never went stumbling on the way to God. Saints with a psyche haunted by monsters and saints with a psyche inhabited by angels have the same fundamental experiences. They speak of God and of themselves in the same terms. They are on the same side of things and in the same world: a world where the only sadness is to experience oneself always as unworthy of God, and where the only joy is to be loved of God and to try to render Him love for love. It is in our eyes, here below, that these two types of saints are different. Before God, they are the same. And this we shall see on the Day of the Lord Jesus.

Must we then decree the vanity of all our psychotherapies and our psychoanalyses, and proclaim that mental health makes no difference in the light of the Kingdom of God? Certainly not because even if, in the end, holiness is a spiritual mystery of grace and liberty that transcend the psyche, it matters that nature be healthy and that it have a certain quality if it is to serve here below as an instrument and sign of life in the Holy Spirit. We must then restore or establish the ability to judge, to feel, and to behave as saints must behave. It is not merely human promotion that presses Christians today to make use of advances in mental health; it is our very faith itself, which tells us that holiness is not only an eschatological mystery that will be revealed on the last day; it is also the actual presence of the Holy Spirit which even now renews the whole man in the image of God. In order for the fruits of the Holy Spirit to ripen today, it is necessary to look to the wholesomeness of the soil.

Think of all who suffer anguish and who need just a bit of balance and of mental freedom in order to be able to grasp the love of God, even a little, in simple human joys, and so begin to practice virtue. If it is true that it may be given them to stammer a yes to Love, even in the psyche’s raging stormy nights, it is no less true that we have an obligation to free them of the burden that makes their universe, redeemed by the Cross of Christ and illumined by the brightness of the Resurrection, an image of hell.

Is it not a thing of grace to allow such persons to perceive even in their psychological profile the dawn of the Resurrection, and to make it possible for them, if not to live in hope, at least to discover what hope is?

*(La sanctification dépend–elle du psychisme?, Louis Beirnaert, Revue Études, Juillet–août 1950, pp. 58–65.)