Agnus Dei Qui Tollis Peccata Mundi: How Jesus transformed the Jewish Liturgical Calendar

The Jewish Pentecost

The Israelite feast of Weeks (called Pentecost in Greek) was observed seven weeks after the feast of Firstfruits, on the fiftieth day. The feast of Firstfruits was the day after the Sabbath that fell in Passover week, that is, the first Sunday after Passover. The number fifty in Israel’s tradition represents an ultimate completion, for it is a Sabbath of Sabbaths, as seven weeks and a day adds up to fifty.

Whereas the feast of Firstfruits consecrates to God the very first fruits of the harvest, the feast of Pentecost (or “Weeks”) offers to God a portion of the whole harvest as a sort of thanksgiving tithe.

In time, this feast would come to commemorate the giving of the law at Mount Sinai as that event took place at the same time of year, a few months after the Passover. This is not just a coincidence: the reception of the law can be seen as the firstfruits harvest of Israel’s Exodus from Egypt. Passover, commemorating the original passover of the Exodus, culminated in the giving of the Law at Sinai.

The First Fruits of the Resurrection

This can be understood typologically in light of the New Covenant. The day of the Firstfruit becomes the Sunday of the Resurrection, the first fruit of Christ’s redemption, for the Sunday on which our Lord rose from the dead was, that year, the feast of First Fruits. Saint Paul seems to be speaking of this when he writes in 1 Corinthians 15:20: “Christ has indeed been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep.”

Fifty Days with the Lord

Throughout those fifty days the Apostles “reaped” those first fruits by living a contemplative life. Fifty days later, as also with the harvest of the fields, these first fruits had multiplied and were ready to be reaped in full. This Christ would do this through the gift of the Spirit.

Reparation for Babel

Christ had already repaired original sin by His death and resurrection, and now, on the day of completion of the Fifty Days (Pentecost), the Holy Spirit makes the final reparation by reversing the curse of Babel with the gift of tongues and fulfilling the promise to bless all nations through Israel. The coming of the Holy Spirit is the new giving of the Law: the Law of Charity prophesied by Jeremiah: “I will give my law in their bowels, and I will write it in their heart…” (Jer 31:33)

The Feast of Tabernacles

So there is a clear continuity in the liturgical year between the Old and the New Covenants from Passover to Pentecost. But wait! there’s even more. In the Jewish calendar, the spring feasts are oriented toward Israel’s history: Passover to the Exodus, Pentecost (or “weeks” to the giving of the law. The fall feasts, however, had taken on an eschatological significance. The day of Atonement prepares for the coming of the Messiah; Tabernacles anticipate the Lord dwelling with his people in the New Kingdom.

The Lamb of God

At the beginning of the Fourth Gospel, Jesus is identified as the “Lamb of God… who takes away the sin of the world.” To a first-century Jew, such a phrase may perhaps have seemed rather odd. Is it really the Lamb that takes away the sin of the world? Is it not rather the goat on the Day of Atonement?1 But here John is actually indicating from the outset of his Gospel that Jesus is fulfilling both roles. He takes the place of both the Passover Lamb and the goat precisely because he is the meeting point between the Old and the New Covenants.

The High Priestly Prayer

John was writing the Fourth Gospel after the other three, and he gives complementary accounts to what is in the Synoptic Gospels rather than repeating them.

John does not give an account of the Last Supper per se, but on that evening he gives Christ’s High Priestly prayer. The High Priestly Prayer of the Lord has striking similarities with what the High Priest does on the day of Atonement:

- The High Priest first prayed for himself,

- then for his family,

- then for all the people,

- and then he was to invoke the Divine Name, YHWH, I AM, three times.

This is just what Jesus does when he says: “Father, glorify Your Son… I have glorified your Name… keep them [the Apostles] in your Name… I pray for these who will know your Name through them.”

Later in the garden, Jesus will also say “I AM” three times and the people will fall to the ground. John is making it clear that Jesus’ new Passover is also a new Day of Atonement.

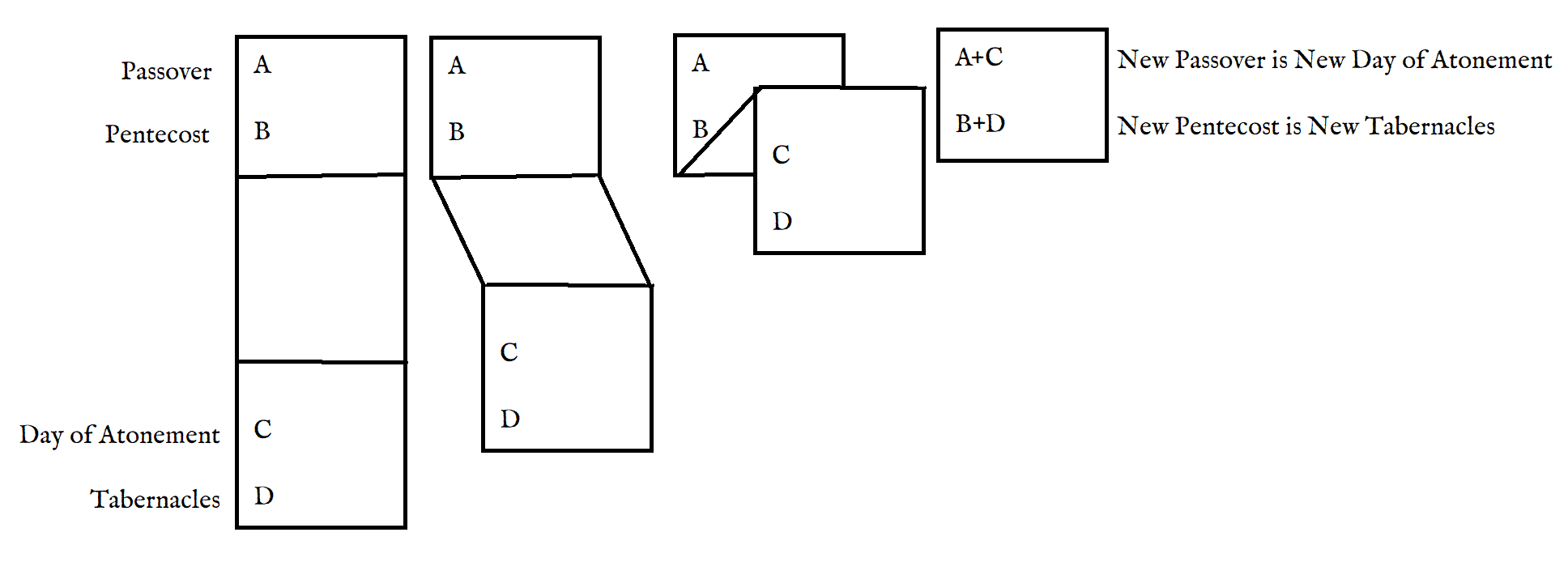

The New Liturgical Calendar

Thus, in bringing an end to the former age, and inaugurating the new eschatological age the two halves of the calendar “fold” onto each other. The memorial and eschatological become a single mystery fulfilled in Christ: Jesus’ new Passover is not just a memorial sacrifice but an atoning sacrifice. On the new Pentecost, the New Law of Charity is enabled through the coming of the Holy Spirit. In a new feast of Tabernacles, a celebration that the Lord has come to dwell in His Own.

“… and I will be their God, and they shall be my people.” (Jer 31:33)

Folding the Feasts Together

We can think of Easter, the Christian Passover, as containing both the Passover of the people of Israel and the old Day of Atonement. Similarly, we can think of the Christian Pentecost as containing both the ancient feast of Pentecost and that of Tabernacles. Easter is both the celebration of the true Exodus and the Lamb of God by whose Blood we are saved from the Egypt of sin and death, and also the day on which the sins of the world are atoned for. Pentecost, likewise, is both the completion of the Passover, the giving of the Spirit of Truth Who writes the law on the hearts of the faithful, and also the celebration that God dwells in us.

The two are folded into one.

The Vigil of Pentecost

On the Vigil of Pentecost, the Church’s lex orandi provides a beautiful confirmation of Our Lord uniting the two halves of the Calendar. The Communion antiphon is as follows:

| Communio

Joannes 7:37-39 Ultimo festivitátis die dicébat Jesus: Qui in me credit, flúmina de ventre ejus fluent aquæ vivæ: hoc autem dixit de Spíritu, quem acceptúri erant credéntes in eum, allelúja, allelúja. |

Communion

John 7:37-39. On the last day of the feast, Jesus said, He who believes in Me, from within him there shall flow rivers of living water. He said this, however, of the Spirit, Whom they who believed in Him were to receive, alleluia, alleluia. |

This scene of our Lord’s words occurred in the Gospel, on the Feast of the Tabernacles; His words were brought to fulfillment in the apostles on Pentecost morning.

We have before shared about the connection between the feast of Tabernacles and the September Ember Day which occurs on the very same date but in a penitential mode. Yet on Pentecost too at the same time, the Church brings before us her fulfillment of this great feast in the coming of the New Law of the Holy Spirit.

Pope Benedict XVI’s Spirit of the Liturgy

Recently, some of our monks have been returning to the Spirit of the Liturgy by Cardinal Ratzinger and discovering new lights that we may have previously missed. In his discussion of sacred time, Ratzinger makes a similar connection between Easter as both a Passover and as a Day of Atonement:

I have already pointed out that, in interpreting the Passion of Jesus, Saint John’s Gospel and the epistle to the Hebrews do not just refer to the feast of Passover, which is the Lord’s “hour”, in terms of date.. No, they also interpret it in light of the ritual Day of Atonement celebrated on the tenth day of the seventh month (September-October). In the Passover of Jesus, there is, so to speak, a coincidence of Easter (spring) and the Day of Atonement (autumn). Christ connects the world’s Spring and Autumn.

A Solution for a Global Liturgy

In context, Ratzinger was exploring how the seasonal aspects of the Christian Liturgical year could accommodate both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. All of the cosmic symbolism of the liturgical year has its origins in the Northern Hemisphere where Easter takes place in spring. Yet with the Gospel spreading over the whole globe, the liturgy is now also celebrated in the Southern Hemisphere where the seasons are switched and Easter comes in the late autumn. If Easter is both the new Passover and the new Day of Atonement, then Christ not only combines the past and future, but also all space and all seasons, both the North and South.

In uniting the memorial and eschatological aspects, heaven opens up to the whole earth. Whereas the Old Law was limited to a small geographical area, and its cosmic significance only made sense there, now the New Law embraces (but without annihilating) all aspects of the cosmos and so unites all geographical areas where “all the ends of the earth have seen the salvation of our God” (Ps 97(98):3).

1See also From the Kippah to the Cross, the autobiographical conversion story of Jean-Marie Élie Setbon from Judaism to Catholicism, where the author at one point wrestles with this very question.↩