100th Anniversary of the Canonisation of Saint Thérèse

Today is the 100th anniversary of the Canonisation of Saint Thérèse of the Child Jesus of the Holy Face.1 The following is an eyewitness account of her canonisation by Rev. Thomas N. Taylor who had the honour of testifying for her beatification process.

May 17, 1925

On the morning of May 17, 1925, Blessed Thérèse, the humble Carmelite of Lisieux, was canonised by her devoted client, Pope Pius XI. The scene was one of such splendour and enthusiasm, that on the morrow His Holiness assured the pilgrims from her own fair land of France that it would not readily be forgotten in Rome, rich ‘though the city was in glorious memories.

Her Beatification

She was beatified…on April 29, 1923, being the first Servant of God whom Pius XI has raised to the Altars. Because of her world-wide popularity, and her extraordinary power, he deliberately chose her to be his first Saint, only two years after the ceremony of her beatification“an event most rare,” he reminded us, “in the annals of the Saints.” It is most remarkable, too, that our Carmelite of Lisieux should be the first daughter of St. Teresa to receive the honour of canonisation. Someone has stated that the Apostle of Assisi had scattered what St. Benedict had gathered into his barns. May it not be said that the roses of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, which sweeten so many lives, are culled in part from the ancient and perfumed rosegardens of the Carmels of the world?

The Day of Her Canonisation

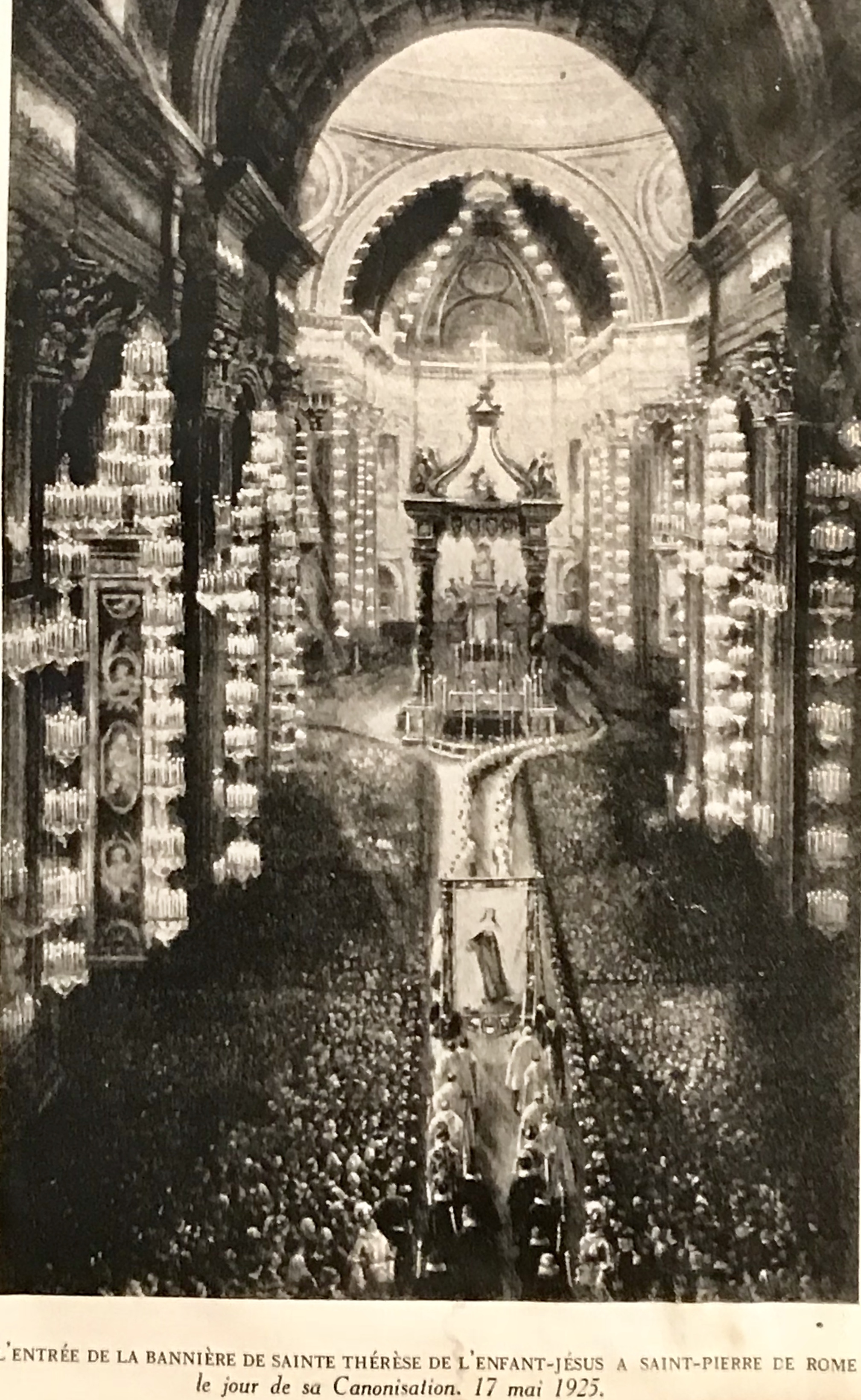

The crowning triumph came on the feast of St. Paschal, like our Saint, the wonderful lover of Jesus Christ in the Blessed Sacrament; and the radiant Roman sunshine was in harmony with the happiness that reigned in the hearts of those privileged to be present at the ceremony. High overhead in the apse of St. Peter’s, a picture of the Blessed Trinity was surrounded by the rays and clouds and angels of the famous “Gloria” of Bernini. Underneath was the bronze chair which covers the chair of St. Peter himself. Below this again was the throne of Pius XI. Myriad clusters of electric lamps made a veritable fairyland of the great Basilica, as the brilliant light fell on the thirty-three scarlet-robed Cardinals, on some two hundred prelates, on the gorgeous Papal Guards, and on the splendour of the Papal Court. Beyond prelates and guards were massed thousands upon thousands of eager faces revealing eager hearts. The preliminaries having been concluded, all immediately rose to their feet. Peter was to speak thtough the lips of Pius.

Pius XI Speaks

Seated and wearing the tiara on his brow, the Supreme Pontiff of the Universal Church replied to the urgent appeal of millions of his children, and the voice, echoed by wireless for the first time at a canonisation, resounded through the vast spaces of the Basilica of Michael Angelo.

“For the honour of the Blessed Trinity and the exaltation of our Holy Catholic Faith; by the authority of Jesus Christ, of Peter and Paul, and by our own authority : after mature deliberation and frequent prayer and consultation with our Venerable Brethren; we declare the Blessed Thérèse of the Child Jesus to be a Saint of God’s Church; and we inscribe her in the catalogue of the Saints on September 30, the day of her heavenly birth.”

Uncontainable Jubilation

The Pontiff ended, in tones of marked emphasis, by the time-honoured words: “In nomine Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti. Amen.” Instantly, and for the first time in the history of canonisations, there came a thunderclap of applause. The trammels of the Process were definitely cast aside, and the queenly daughter of Carmel’s Queen found upon earth the freedom and high honour that had long since been her portion in Paradise. It seemed as if the multitude could not contain its joy at the thought of the new life dawning for the apostle of the Child Jesus. Indeed, the message of the Holy Father recalled the music of the Bethlehem sky, and our souls exulted as we dreamed we heard again the heavenly anthem: “Gloria in excelsis Deo, et in terra pax!” Simultaneously the silver trumpets sounded far away in the dome, and the great bells of the Basilica rang out in the morning air, their joyous notes echoed for the space of an hour by all the bells of Rome. Over mountains and seas ten million hearts caught up the echo and sang their gratitude to the Creator of St. Thérèse. And of all those canticles of praise none were more grateful than those of her three Carmelite sisters in a convent of Lisieux, and of one Visitandine in Caen; and of these again the most heartfelt was surely the thanksgiving of Mother Agnes of Jesus, her “little mother,” for the glory given to “little Thérèse.”

The Mass

Shortly after the Te Deum, there began that scene of indescribable splendour, the Mass of a newly canonised Saint sung by the Vicar of Christ. To and fro through ranks of great prelates, noble guards, and knights in scarlet uniforms or flowing white mantles, the Holy Father passed and repassed from throne to altar and from altar to throne. Above the Papal altar stood the celebrated canopy of bronze, and high aloft towered the most marvellous dome in all the world. In the crypt underneath, the precious remains of St. Peter and St. Paul lay awaiting the hour of their resurrection.

From the princes of earth in the tribunes—Ireland’s first Governor-General was there—and from the multitude from many lands in apse and nave—the Cardinals of Westminster and Philadelphia brought the homage of two nations—one’s mind travelled to the cloud of unseen witnesses. She herself, Carmel’s humblest child, was watching her Eucharistic Spouse as He gave thanks to His Father for the graces lavished on the “Little Flower of Jesus.” She noted each pilgrim in the Basilica where less than forty summers before she had knelt, a simple child of fourteen years. She noted, likewise, each one of the countless throbbing hearts outside its walls uplifted to her on this her day of triumph. Her blessed parents, with their four angel children, together with her favourite martyr friends, Agnes and Cecilia of Rome, Joan and Théophane of France—all these were looking down.. So, also, were her Spanish Saints, Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross—it was their first coronation of a daughter in Christ, after three centuries and a half. So, too, were Our Lady of Carmel [sic], and the Heavenly Father to whom St. Thérèse had refused nothing since the age of three.

After the Gospel of the Mass, Pope Pius preached on her whom he had already called a “miracle of virtues and a prodigy of miracles.” It was a glowing tribute of praise. Scarcely had he finished, when in the presence of the vast audience there descended a token of thanks. The Saint had loved flowers passionately from childhood. They mirrored dimly her Divine Lover’s beauty. In Carmel she loved chiefly the rose, queen of all flowers. She taught her novices to love it too, for was it not the emblem of divine charity, queen of all virtues? Plucking the rose-petals she would scatter them around her crucifix, images of the life she longed to sacrifice, every instant of it, for Christ her Beloved. On her death-bed she promised that she would spend her Heaven raining roses upon earth. How often since that prophecy has not their sweet odour betokened her mysterious presence to her clients! Indeed, one of the two Beatification miracles had been heralded by a shower of real roses—a great picture in St. Peter’s reproducing the scene.

Roses Fall on Their Own

As the amplifiers ceased to echo the Pope’s panegyric of St. Thérèse and her “little way” to holiness, suddenly the roses came again. Five of those which decorated a cluster of lights in the apse detached themselves in some unknown way, then, describing a large curve in the air, they landed at the Pontiff’s feet. A thrill passed through the great assemblage. The sign was as gracious as it was characteristic. The Rose Queen was rendering her thanks.

Soon after took place the presentation by the Cardinals of the traditional offerings—decorated candles, bread, wine, and in silvered or gilt cages, little birds symbolical of the aspirations of the Saint. One of the cages, with its two turtle-doves, found its way later to the Carmel of Lisieux. At the Communion the Holy Father shared at the throne the consecrated Host and Chalice with his cardinal deacon, using the golden tube for the Precious Blood.

The Mass ended with the Papal blessing and the stately procession re-formed. Four thousand were said to have taken part in it. The cheering burst forth again, and came in waves that eddied lovingly around the gigantic edifice until the retainers bore Pius XI on the lofty sedia back to the Vatican. The coronation was over, but the lights remained in order that the two hundred thousand who had failed to gain admission to the ceremony might still behold the splendour of the illuminated Basilica.

Although we had taken our places in St. Peter’s at half-past six, and it was now almost two o’clock in the day, still we lingered on, unwilling to snatch ourselves away from the scene that seemed to foreshadow our unwearying vision of the “ Little Queen” in the eternal courts of God.

1Saint Thérèse sometimes wrote her title as “of the Child Jesus and of the Holy Face”, but her preferred style seems to be to leave out the and. For instance, between Letters 122 and 129, she uses the and in LT 124, but she writes it without the and in LT 122, LT 126, LT 127, and LT 129. Perhaps the reason for this was because it was actually two titles, and not a single title, but including the and makes it seem like it is a single title. ↩