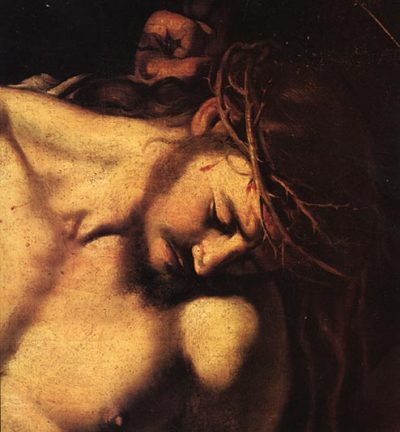

Obœdiens usque ad mortem (VII:7)

Jan. 1 June. 1 Oct.

The third degree of humility is, that a man for the love of God submit himself to his superior in all obedience; imitating the Lord, of Whom the apostle saith: “He was made obedient even unto death.”

The Third Degree of Humility tells us that a monk’s submission to his superior in all obedience, for the love of God, is what makes a monk like Christ. Saint Benedict quotes Saint Paul’s hymn in celebration of the self–emptying κένωσις and glorification of Christ, the Christus factus est, that we sing again and again during the Sacred Paschal Triduum:

Let this mind be in you, which was also in Christ Jesus: Who being in the form of God, thought it not robbery to be equal with God: But emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being made in the likeness of men, and in habit found as a man. He humbled himself, becoming obedient unto death, even to the death of the cross. For which cause God also hath exalted him, and hath given him a name which is above all names: That in the name of Jesus every knee should bow, of those that are in heaven, on earth, and under the earth: And that every tongue should confess that the Lord Jesus Christ is in the glory of God the Father. (Philippians 2:5–11)

Therein we are given the pattern of Benedictine obedience. This is the true sequela Christi, the following after Christ ad gloriam (Prologue: 7), even unto glory, that is itself an effect of grace, for not only does Our Lord say, “If any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross daily, and follow me” (Luke 9:23); He also says, “No man can come to me, except the Father, who hath sent me, draw him; and I will raise him up in the last day” (John 6:44). Our Lord communicates the grace to follow Him in a single loving glance — Jesus autem intuitus eum (Mark 10:21) — which draws one after Him, leaving one free, all the same, to respond or not to His invitation.

A certain man running up and kneeling before him, asked him, Good Master, what shall I do that I may receive life everlasting? And Jesus said to him, Why callest thou me good? None is good but one, that is God. Thou knowest the commandments: Do not commit adultery, do not kill, do not steal, bear not false witness, do no fraud, honour thy father and mother. But he answering, said to him: Master, all these things I have observed from my youth. And Jesus looking on him, loved him, and said to him: One thing is wanting unto thee: go, sell whatsoever thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me. Who being struck sad at that saying, went away sorrowful: for he had great possessions. (Mark 10:17–22)

Saint Benedict says that a monk’s submission to his superior in all obedience is driven by the love of God. In this, also, does a monk, by grace, imitate Our Lord, who said before His Passion:

But that the world may know, that I love the Father: and as the Father hath given me commandment, so do I. Arise, let us go hence. (John 14:31)

A monk is not submissive to his superior in all obedience because he suffers from a kind of psychological deficiency that makes him crave a servile dependence on another, or because obedience gives him some kind of emotional security. A monk is not driven by an inability to make decisions that compels him to say at every turn, “Tell me what to do”. Monastic obedience is a free act engaging the mind and the heart; it is, as Saint Benedict teaches in Chapter V, characteristic of those who love Christ. “The first degree of humility is obedience without delay. This becometh those who hold nothing dearer to them than Christ” (Chapter V: 1–2).

A monk freely chooses obedience, thereby exercising his will, because Christ chose obedience, and because one who lives with Christ and contemplates Him in the Gospels and in the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar, sees that His obedience is the expression of His love of the Father. “That the world may know, that I love the Father: and as the Father hath given me commandment, so do I” (John 14:31).

Mother Mectilde was graced with profound insights into the psychology of obedience under grace. Not for nothing has she been called “the Teresa of the Benedictine Order”. Like the saint of Avila, Mother Mectilde had a remarkable ability to probe souls and to explain souls to themselves. Like the saint of Avila, she was forthright and direct. Mother Mectilde writes incisively to a complicated and scrupulous religious of the rue Cassette:

Mother Mectilde was graced with profound insights into the psychology of obedience under grace. Not for nothing has she been called “the Teresa of the Benedictine Order”. Like the saint of Avila, Mother Mectilde had a remarkable ability to probe souls and to explain souls to themselves. Like the saint of Avila, she was forthright and direct. Mother Mectilde writes incisively to a complicated and scrupulous religious of the rue Cassette:

Truly, you are very far from religious simplicity and from the spirit of your holy Rule, which orders you to obey simply and to submit your judgment to your superiors. I am not in the least surprised that you should have so many troubles, because you foment them in yourself and you attract them to yourself by attachment to your own perception of things. It is absolutely necessary that you abandon yourself in all simplicity to holy obedience, and that you make an effort, with regard to your reason and to the natural lights of your mind, to submit yourself. This is what God wants of you absolutely; you must make up your mind to do this. Otherwise, you will remain yet a long time just as you are, and maybe even your whole life, unless by some blow of the mercy of God, which He can do by His all–powerful mercy, but which He will not do in some miraculous way, because you have the ordinary and actual grace for that yourself.

To Mother Marie de Jésus Chopinel, another religious of the rue Cassette, Mother Mectilde writes with her characteristic honesty:

All your bent must be to get out of your own mind (esprit), by a faithful abnegation and renunciation of your own thoughts and your own lights. Become like a little child in submission. Leave behind your fears; they only get in the way of your going forward. Leave your perfection to the conduct of obedience; do exactly what you are ordered. If only you could understand the inexpressible happiness of being nothing in all things and everywhere, you would find and would possess a good known only to souls who want to lose everything so as to rejoice in the eternal peace that proceeds from the possession of God.

The subtext of what Mother Mectilde writes is the Holy Rule with its Christological focus. Mother Mectilde, however, at least in these two fragments of her correspondence, does not speak explicitly of Jesus Christ. Mother Mectilde, in fact, more often than not speaks simply of God. She does this not because she is a deist making abstraction of Christ, but because she is in Christ. “And I live, now not I; but Christ liveth in me. And that I live now in the flesh: I live in the faith of the Son of God, who loved me, and delivered himself for me” (Galatians 2:20). Mother Mectilde thinks, and writes, and speaks from the Heart of Christ. She has in her, as Saint Paul says, “the mind that was in Christ Jesus” (Philippians 2:5).

The monk who submits himself to his superior in all obedience in order to be like Christ, will soon find that he is acting in Christ and that he is with Christ. He who is in Christ will live out in his flesh the mystery of Christ’s Passion, even as Saint Paul did: ” I fill up those things that are wanting of the sufferings of Christ, in my flesh, for his body, which is the Church” (Colossians 1:24). The obedient monk abides in Christ: “If any one love me, he will keep my word, and my Father will love him, and we will come to him, and will make our abode with him” (John 14:23). Monastic obedience is, then, a kind of sacrament that makes us like Christ, that gives us Christ, and that unites us to Christ. Obedience is that by which we unite our bodies to the Body of Christ, our souls to His soul, our minds to His mind, and our hearts to His Heart, and this for the glory of His Father and for the love of Christ’s Body and Bride, the Church.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)